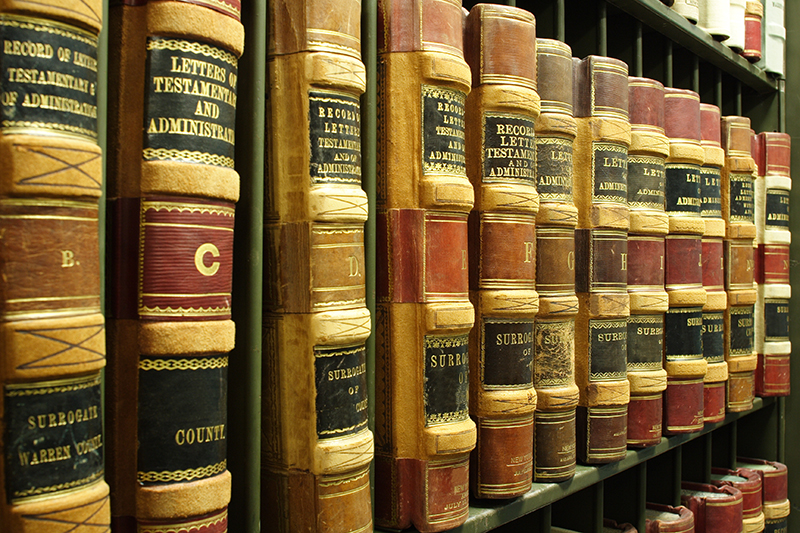

Legal books. (Photo: ebay)

Retroactivity of California Statutes

The California Supreme Court must not have ruled on the statute in question

By Chris Micheli, October 7, 2020 6:24 am

In California, as in most states, a statute is presumed to operate prospectively. Quarry v. Doe I (2012) 53 Cal.4th 945, 955. In construing statutes, there is a presumption against retroactive application unless the Legislature plainly has directed otherwise by means of express language of retroactivity or other sources that provide a clear and unavoidable implication that the Legislature intended retroactive application of the statute. Id.

In addition, a statute should be construed to preserve its constitutionality. In re York (1995) 9 Cal.4th 1133, 1152. The burden of establishing the unconstitutionality of a statute rests on the party attacking it, and courts may not declare a legislative classification invalid unless, viewed in the light of facts made known or generally assumed, it is of a character that precludes the assumption that the classification rests upon some rational basis within the knowledge and experience of the legislators. Id.

The California Civil Code includes a specific codification of this general principle by stating in Section 3, “No part of this Code is retroactive, unless expressly so declared.” Moreover, the presumption against retroactivity applies with particular force to laws creating new obligations, imposing new duties, or exacting new penalties because of past transactions. In re Marriage of Reuling (1994) 23 Cal. App. 4th 1428, 1439.

Based upon recent decisions by the California Supreme Court, the general rule in this state is that, if the Legislature clearly indicated its intent that an amendment to a statute is to be applied retroactively, then a court generally must honor that intent unless there is a constitutional objection to doing so. “The presumption against statutory retroactivity has consistently been explained by reference to the unfairness of imposing new burdens on persons after the fact.” Landgraf, at p. 270, 114 S.Ct. 1483.

This is not to say that a statute may never apply retroactively. “[A] statute’s retroactivity is, in the first instance, a policy determination for the Legislature and one to which courts defer absent ‘some constitutional objection’ to retroactivity.” Myers, 28 Cal.4th at p. 841, 123. As such, the basic rule in California is that “a statute may be applied retroactively only if it contains express language of retroactivity or if other sources provide a clear and unavoidable implication that the Legislature intended retroactive application.” Id.

The California Supreme Court has made the statement that “where a statute provides that it clarifies or declares existing law, ‘[i]t is obvious that such a provision is indicative of a legislative intent that the amendment applies to all existing causes of action from the date of its enactment. In accordance with the general rules of statutory construction, we must give effect to this intention unless there is some constitutional objection thereto’.” Western Security Bank, 15 Cal.4th at p. 244.

California courts look to the text of the bill and legislative materials to determine whether the later enacted bill made a change in the law or whether the later enacted bill clarified existing law. If the bill represents a clarification of existing law, then the bill is applied to all instances, both retroactively and prospectively. If the bill enacts a change in the law, then the court looks to determine whether the Legislature intended for the law change to be applied retroactively. In this regard, the court basically asks, did the Legislature make a clear intent to apply the amendment retroactively?

As a result of these appellate court decisions, three main points can provide guidance to lawmakers and bill drafters when attempting to make retroactive changes to California statutes:

- Did the Legislature enact the change in law promptly after the adverse court decision? In most instances, the legislative change needs to be made within a few months of the court decision.

- Has the Supreme Court rendered a final decision? If yes, then the legislative enactment is most likely to be deemed only prospective in application.

- Is there some amount of ambiguity in the statute that was amended? The courts are usually more inclined to allow a retroactive law change when an ambiguous statute was amended by the Legislature.

Based upon these appellate court decisions and the guidance issued, the Legislature does have the authority to retroactively declare that certain statutory changes can be applied retroactively, but only in certain specified instances. The most important point is that the California Supreme Court must not have ruled on the statute in question. Otherwise, the Legislature can only make a prospective change in the law.

- Frequently Asked Questions about When Elected Officials Take Office - April 25, 2024

- Frequently Asked Questions About Ethics Training for Local Agencies - April 24, 2024

- Frequently Asked Questions about Privileges of Voters in California - April 23, 2024