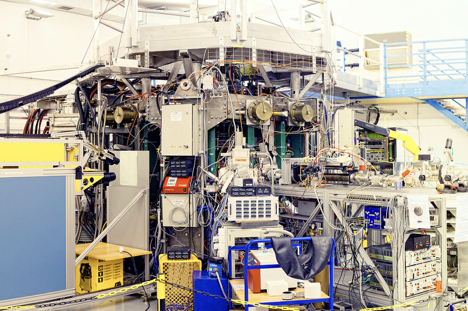

The daunting complexity of harnessing the energy of stars is evident in this photo of a tokamak, one possible design for a fusion reactor, from the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics. (Photo: BigStockPhoto.com)

Nuclear Fusion: Holy Grail of Energy, or Waste of Time and Money?

As the climate-change clock ticks closer to midnight, it’s time to cut our losses and go with what works

By Carl Wurtz, March 7, 2023 2:45 am

Two weeks ago, Assemblywoman Lisa Calderon (D-Los Angeles) introduced Assembly Bill 1172, a bill that would require state energy commissions to analyze the feasibility of using nuclear fusion to help meet California’s climate goals. “Nuclear fusion?” you ask. “Isn’t that the energy that powers the Sun? Wasn’t that a big deal back in the 19XXs [pick a decade]?”

Or, you might remember a wave of press releases in early December, when scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), with a brief shot of energy from the world’s most powerful laser, raised the temperature of hydrogen in a tiny cylinder to a mind-bending 180 million degrees Fahrenheit – 1,700 times hotter than the surface of the sun – and for the first time in history, were able to trigger a sustained fusion reaction that produced more energy than it consumed.

If both experiences come to mind, it’s understandable. Nuclear fusion has captured the public’s attention on and off since the 1930s, when physicists first identified it as the source of light radiating from stars. Interest in peaceful uses for the power of the atom grew, and by the early 1950s, the possibility of harnessing fusion for the purpose of generating electricity was gaining popularity. With an endless supply of fuel (hydrogen can be made quickly and economically from water), and the seemingly boundless supply of energy it produced, the benefits of fusion seemed limitless. The viability of nuclear fission, where atoms of uranium are split to produce energy, had already been demonstrated – yet misperceptions persisted. A skittish Cold-War public believed uranium might be stolen and used to manufacture nuclear weapons. Fearful opponents thought leftover spent fuel – highly-radioactive racks of metal rods – might somehow leak into the ground, and poison water supplies.

Nuclear fusion thus came to symbolize “clean” nuclear energy. Since the 1950s, the U.S. has spent an estimated $20 billion on fusion research; today $700 million is included in the federal budget. Though progress in the last 70 years has been substantial, solutions to several key challenges remain stubbornly out of reach.

That hasn’t deterred private investors from jumping into the fusion game with both feet. Internationally, 31 companies are racing to have the first practical fusion reactor in production, with investment setting new records each year. In 2021, private investment was $2.6 billion; in 2022 companies welcomed at least $3.4 billion more, including substantial investments from mega-billionaires Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos.

With investors parting with capital at a dizzying rate, practical fusion energy seems to be just around the corner. We should soon be able to generate unlimited electricity from tap water, and never have to worry about electric bills or outages again. Shouldn’t we?

That depends on whom you ask.

Physicist/author John P. Holdren began his career as a plasma physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in 1970, and has since amassed a stellar record of achievement, both in academia and public service. He served as Science Advisor to Presidents Clinton and Obama, and has authored or co-authored 18 books, encompassing disciplines as diverse as fusion and fission energy, arms control, environmental sciences, and public policy.

After the announcement of LLNL’s breakthrough in December, Holdren released a statement titled “Fusion Breakthroughs in Context”, in which he tempers the aura of speculative excitement around fusion with some needed perspective. He writes:

“Harnessing these reactions on Earth’s surface to help meet society’s energy needs has proven to be incredibly challenging.”

He then explains why achieving a sustained reaction with high-powered lasers still faces a long and arduous journey:

“A practical fusion reactor based on this approach would need 10-20 times more fusion yield per shot than the electricity supplied to the laser, hence 2500-5000 times the yield of the Livermore experiment, and it would need to operate at rate of about 10 shots per second. The current Livermore device can manage 2 shots per day [emphasis in original].”

Holdren harbors more hope for other fusion technologies, however:

“The magnetic approach to controlled fusion…is actually considerably closer than laser fusion to achieving reactor-relevant yield…”

And he compares it to other clean-energy alternatives, noting that it is “less polluting than fossil fuels,” and is “free of the intermittency and land requirements of wind and solar.”

Yet he offers a sober appraisal of fusion’s street-date:

“It seems very unlikely that fusion reactors of any type will be contributing significant electricity to the power grid before the second half of this century; and, even on that timescale, it is not obvious that they can be made both reliable and inexpensive enough to compete with other options.”

Among all the resources jockeying for position in the lucrative U.S. energy market, what fusion lacks is certainty. It’s a commodity with more questions than answers, a speculative curiosity that never seems to arrive at its destination.

A common homily cited in energy circles is that the technology has been “thirty years away for the last seventy years.” Though trite, is has foundation in fact.

Asm. Calderon’s bill is a reasonable request, but it would be a mistake to allow fusion to distract from growing interest in nuclear fission, the variety which already provides 20% of U.S. electricity. A safe and proven technology, nuclear fission has become the only realistic option for meeting California’s climate goals. With the growing imperative of lowering CO2 emissions, and after spending decades and billions of dollars on ineffective carbon-free alternatives, there’s no more money, or time, to waste.

Successful nuclear fission has been “right around the corner” for100 years.

The so far insurmountable goal is to duplicate the amount of gravity using “Earth-available” resources to compresses matter enough that fission can occur and “create a star” in a fancy and expensive test tube.

Good luck with that.

Fission has already been harnessed to generate electricity at enormous capital and operating costs. Fission is breaking atoms apart and using the energy released to heat something that turns a turbine.

Fusion is smashing atoms together and using the research money to make payments on a sick BMW and a time share in Cancun.

That’s a good one! What a good way to remember the difference and to know what is actually going on here.

Assemblywoman Lisa Calderon from LA might be getting lucrative financial incentives to promote nuclear fusion with billions of dollars being spent including substantial investments from mega-billionaires like Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos? Maybe she’ll be able to buy an ocean front estate in Cancun?

Nuclear fusion is a subsidy dumpster. The point of the enterprise is to burn heaps of borrowed money to ensure the eternal slavery of future generations to the Federal Reserve and their proxies.