How One Candidate Beat the Odds in the One Party State of California

‘We invested in talking to voters directly, and made sure we had a message that speaks to voters’

By Edward Ring, December 24, 2022 7:54 am

Anyone who thinks it is impossible for Republicans in California to regain relevance has not studied the campaign, and improbable victory, of Josh Hoover. The odds were against Hoover, who ran against a seasoned incumbent Democrat, five term Assemblyman Ken Cooley. The redrawn 7th District, with 38 percent registered Democrats versus 32 percent Republicans, favored Cooley. To make matters much more challenging, Cooley’s campaign spent $4.8 million compared to Hoover’s $1.7 million.

Hoover won by 1,383 votes, less than one percent, and how he did it is a case study in how California’s Republican candidates can win despite having far less money and a registration disadvantage. Reached by phone earlier this week, Hoover said that while there were a lot of factors in the race that came into play, the most obvious explanation for his victory was that he simply outworked his opponent in making direct contact with individual voters. The Hoover campaign mustered far more people to send texts, make phone calls, and walk door to door.

Cooley, by contrast, during the final month was spending over $250,000 per week on television and radio ads. Throughout the campaign Cooley was mass mailing expensive campaign flyers. Cooley’s campaign relied on mudslinging, like so many do, but it may have backfired on him. When a household has received over dozen flyers attacking Josh Hoover as a Trumpian misogynistic book burning extremist, they’re taken aback when they meet the candidate and realize he’s not a monster at all, but a genuine, humble, reasonable, thoughtful person who cares about the people living in his district.

As Hoover put it, “Cooley never attacked me on anything I ever did, he created generic talking points on why Republicans are bad and tried to paint them over who I am. It didn’t resonate because it wasn’t believable.” No. It wasn’t. Not when the target of the unfounded attacks has walked precincts, knocked on thousands of doors, and met voters face to face.

Hoover, who along with hundreds of volunteers, knocked on over 40,000 doors during his campaign, didn’t have the funds to match Cooley punch for punch on the air. Instead he put campaign resources into calling every grassroots activist organization in the region that would support him, and recruited volunteers. His campaign staffers called every potential source of volunteers not once, but every week throughout the summer and fall. If any organizations, such as the county GOP, provided Hoover their volunteer list, then every person on that list was called regularly. It worked. During the final weekends of the campaign, Cooley had at most 50 people in the field. By contrast, throughout the late summer and through the first weekend in November, Hoover was consistently sending over 100 people out to walk precincts.

Not only did Hoover’s team recruit volunteers from the county GOP office, from GOP legislative staffers, from local tax fighting groups, and other activist groups, but he also set up internship programs at the local colleges and high schools, where scores of additional teenagers and young adults were recruited to engage in direct voter contact.

Along with prioritizing putting limited resources into building up a bigger ground game than his opponent, Hoover focused on a positive message. When forced to respond to negative ads that were attacking him as a bad person, Hoover’s flyers instead attacked Cooley on his record and his actions. But Hoover’s primary message, consistently expressed in direct voter contacts, was that he cared about the same issues as his voters – quality education, public safety, homelessness, the cost of living.

When Cooley made a late pivot to claim he would clean up the homeless encampments along the American River, it was easy for Hoover to respond. After all, Cooley has been in the state legislature for ten years, and the situation has not improved.

There were some factors helping Hoover that may or may not be replicable in other districts. The new 7th district incorporates a lot of walkable suburbs, making it easier for a volunteer to knock on hundreds of doors in a single day. The redistricting cut away some of Cooley’s reliable blue communities and replaced them with Fair Oaks (purple), and Orangevale (red). Even in Folsom, also added to the 7th District and mostly blue, Cooley was starting from scratch and had no advantages of incumbency.

There may have been complacency in Cooley’s campaign, but until Republicans start winning more races, Democratic complacency may benefit any Republican trying to beat the odds. When asked repeatedly how he won, Hoover was consistent, “we knew from the beginning we would not leave anything on the field,” he said, “no stone unturned in regards to volunteer effort and ground game. We invested in talking to voters directly, and made sure we had a message that speaks to voters with kitchen table issues rather than a partisan message. Our message was that we care about the people in our community and we want to put forward solutions.”

In California, Every Voter is Fair Game

Another key strategy Hoover adopted from the start was to consider every voter fair game. In a strategy that informed both their message and how they prioritized which households and neighborhoods to send door knockers, they set a goal to attract 10 percent of registered Democrats, plus all no-party-preference voters.

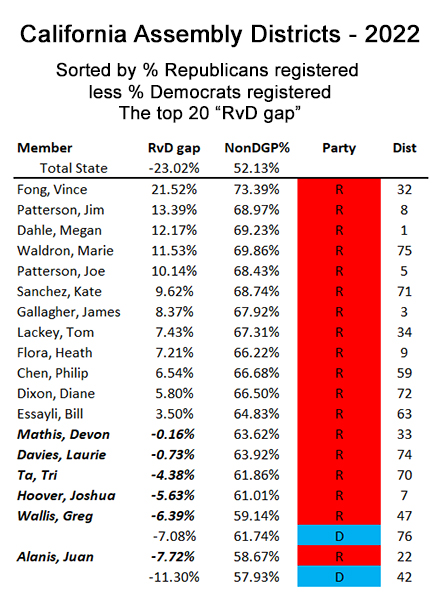

There is a subtle but important difference between the registration landscape based on which party has more registered voters, versus one based on how many voters are not in the opposition party. This comparison is useful in California since registered Democrats greatly outnumber registered Republicans. The first chart, below, is sorted from registration data on all 80 Assembly Districts. It shows the twenty districts in the California Assembly that have the highest values when subtracting the percent Democrat registration from the percent Republican registration. The percentage difference shows in column one (RvD gap). This is a traditional way of evaluating a candidate’s chances.

As can be seen on the above chart, the 18 Republicans that won this November all did so in the districts where Republicans have the strongest registration. That would include, however, six victorious Republicans (names italicized) that won in districts where there were more registered Democrats than Republicans. Juan Alanis, in the 22nd District, was able to prevail despite a 7.72 percent registration disadvantage. But maybe, in this era of widespread and growing bipartisan dissatisfaction with failing Democratic policies, the registration advantage or deficit isn’t the only way to view a Republican candidate’s prospects.

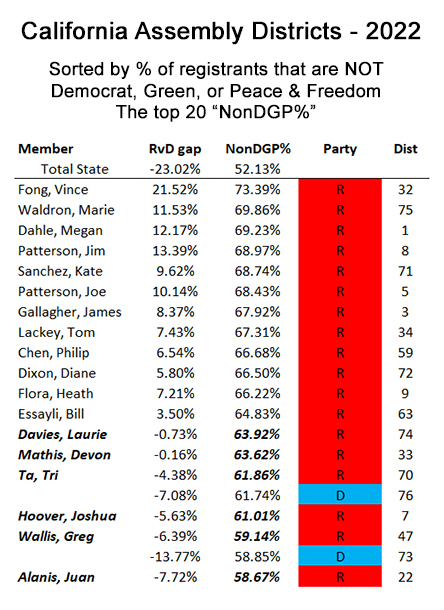

The next chart, below, presents the same data, but this time sorted by column two, which calculates the percentage of registrants in each district that are not registered as either Democrats, Greens, or the Peace and Freedom parties (“Non DGP”). Sorted this way, the roster doesn’t shake out much differently, but the approach this represents is the future. Every voter is in play, and for targeting and messaging, the prevailing question is how many voters have proclaimed themselves to be either liberal or progressive, and how many have not.

This second chart reflects Hoover’s strategy. The results are interesting on both charts. They show that in all 12 districts where there was a GOP advantage, the GOP candidate won, and that in six cases, Republican candidates won in districts where there was a Democrat advantage. Republicans should study the tactics of all six candidates who beat the metrics, i.e., had negative GOP percentages and high absolute numbers of Democrat voters – they are Devon Mathis (33), Laurie Davies (74), Tri Ta (70), Josh Hoover (7), Greg Wallis (47) and Juan Alanis (22).

If six Republican Assembly candidates could beat the odds this time, what if next time every Republican Assembly candidate emulated Hoover’s strategy, aspiring to attract every independent or Republican voter, along with 10 percent of the Democratic (or Green or P&F) voters? Were all of them to fully succeed in this objective, then two years from now, Republicans would control 71 seats in the Assembly. Strategists may pick their number, and ratchet that goal down to whatever reality they’re comfortable with. But this is not fantasy.

Democrats are destroying California. Most voters have figured that out, and are waiting for politicians to step up with solutions. Registered Republican voters constitute a super-minority in California, but Republican candidates can still win if they stick to the issues that concern everyone, and make their case on the ground. Josh Hoover proved it.

- Ringside: What Will California Gas Prices Do in 2026? - February 19, 2026

- Ringside: Large Scale Desalination Belongs in California’s Water Strategy - February 12, 2026

- Governor Newsom: Turn Up the Delta Pumps! - February 11, 2026

Where did you get the charts in the article titled “How One Candidate Beat the Odds in the One Party State of California”? or the information if you made the charts?