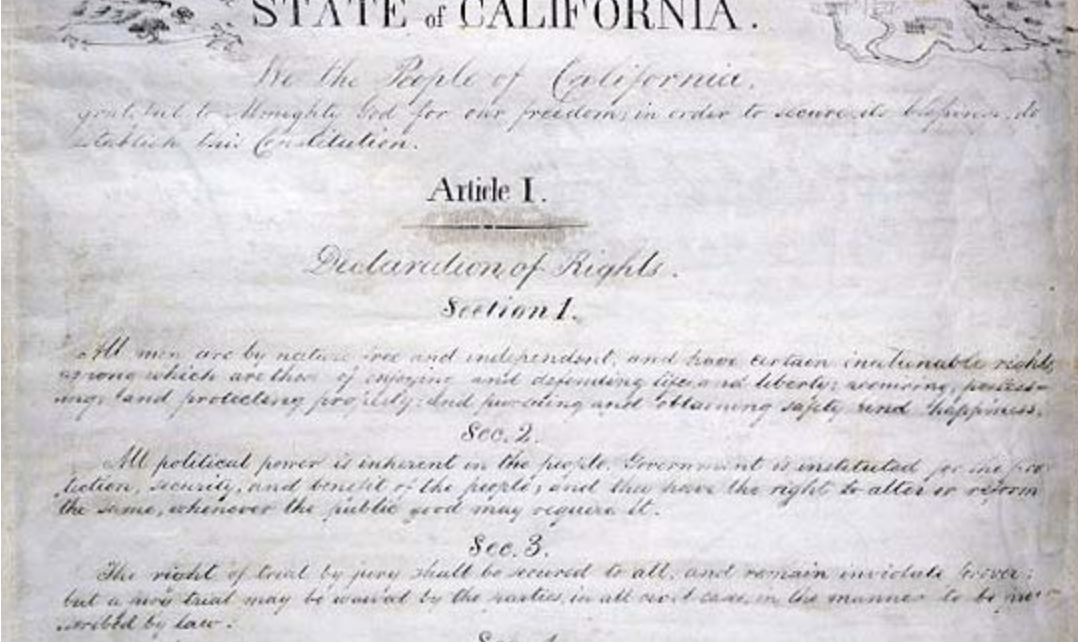

California Constitution. (Photo: www.sos.ca.gov)

California Courts and the Legislature Amending an Initiative Statute

By Chris Micheli, December 26, 2024 7:39 am

California’s Constitution, in Article II, Section 10(c) sets forth the authority of the Legislature to change the language of a statutory initiative (i.e., an initiative passed by the voters that added or amended statutory language, rather than a constitutional initiative). Section 10(c) provides, in part: “The Legislature may amend or repeal an initiative statute by another statute that becomes effective only when approved by the electors unless the initiative statute permits amendment or repeal without the electors’ approval.”

This state constitutional provision limits the ability of the Legislature to make any changes to statutes enacted by the voters. The first part of Subdivision (c) provides that the Legislature can only amend or repeal an initiative statute if their proposed legislative changes are approved by the voters, which would occur on a statewide ballot. The second part of Subdivision (c) contains an exception to this general rule: if the initiative statute allows amendment or repeal of its provisions without voters’ approval, then the Legislature can do so.

Note, however, that most initiatives only allow legislative amendment with a higher vote threshold by the members of the Assembly and Senate (most often it is 2/3, but sometimes an even higher vote threshold) and that the legislative amendments “furthers the purposes (or intent) of the statutory initiative.” As a result, the Legislature’s ability is still strictly limited. So,, how have California courts considered this constitutional limitation?

In County of San Diego v. Commission on State Mandates (2018), the California Supreme Court dealt with a voter-approved statutory initiative, which was followed by legislative amendment. The high court first explained the constitutional provisions. “The strict limitation on amending initiatives generally … derive from the state constitution. Article II, section 10, subdivision (c) of the California Constitution provides that an initiative statute may be amended or repealed only by another voter initiative, ‘unless the initiative statute permits amendment or repeal without the electors’ approval.’ The evident purpose of limiting the Legislature’s power to amend an initiative statute ‘is to “protect the people’s initiative powers by precluding the Legislature from undoing what the people have done, without the electorate’s consent.’ (Shaw v. People ex rel. Chiang (2009) 175 Cal.App.4th 577, 597) But we have never had occasion to consider precisely “what the people have done” and what qualifies as “undoing” (ibid.) when the subject is a statutory provision whose reenactment was constitutionally compelled under article IV, section 9 of the Constitution.”

The Supreme Court went on, “The State respondents’ argument depends on one crucial assumption: that because of article II, section 10, subdivision (c) of the state Constitution, none of the technically restated provisions may be amended, except as provided in the initiative’s amendment clause. Yet the parties and amici curiae California State Association of Counties and League of California Cities have identified at least nine legislative amendments to statutes technically restated in Proposition 83 that — under the view espoused by State respondents — would be in violation of the initiative’s amendment clause. (See Voter Guide, supra, text of Prop. 83, § 33, p. 138.) These amendments contained provisions that neither expanded the scope of the initiative, increased the punishment, nor garnered a two-thirds vote of each house. (citations omitted) If the State respondents are correct that any amendment to a provision that happens to have been technically restated in a ballot measure must follow the amendment process provided in the initiative, then all of these amendments would be invalid.

In the Shaw case, “as the Court of Appeal readily observed, the Legislature’s 2007 amendment was suspect for a specific reason: it sought to undo the very protections the voters had enacted in Proposition 116. (Shaw, supra, 175 Cal.App.4th at pp. 597-598) Unlike Proposition 83, Proposition 116 had not merely restated a key provision without change. Rather, Proposition 116 had added language to Revenue and Taxation Code section 7102, subdivision (a)(1) designating the PTA as ‘a trust fund,’ and elsewhere stated that the funds were available ‘only for transportation, planning and mass transportation purposes.’” (Shaw, at p. 589, 96 Cal.Rptr.3d 379.)

“So when the Legislature –– a decade and seven years later –– sought to undermine the voter-created trust fund by adding new provisions to divert those funds from uses the voters had previously designated, it was not amending a provision that had merely been technically restated by the voters. (Shaw, at p. 597, see id. at p. 601, [“The voters’ intent to preserve spillover gas tax funding of the PTA would be frustrated if the Legislature could amend section 7102, subdivision (a)(1) to modify the amount of spillover gas tax revenue making it to the PTA.”].)

“By contrast, nothing in Proposition 83 focused on duties local governments were already performing under the SVPA. No provision amended those duties in any substantive way. Nor did any aspect of the initiative’s structure or other indicia of its purpose suggest that the listed duties merited special protection from alteration by the Legislature. According to the Voter Guide, the intended purpose of Proposition 83 was to increase penalties for violent and habitual sex offenders; prohibit registered sex offenders from residing within 2,000 feet of a school or park; require lifetime electronic monitoring of felony registered sex offenders; expand the definition of an SVP; and change the then-existing two-year commitment term for SVPs to an indeterminate commitment. (Voter Guide, supra, official title and summary of Prop. 83, p. 42.)

“A more prudent conclusion is to assign somewhat more limited scope to the state constitutional prohibition on legislative amendment of an initiative statute. When technical reenactments are required under article IV, section 9 of the Constitution — yet involve no substantive change in a given statutory provision — the Legislature in most cases retains the power to amend the restated provision through the ordinary legislative process. This conclusion applies unless the provision is integral to accomplishing the electorate’s goals in enacting the initiative or other indicia support the conclusion that voters reasonably intended to limit the Legislature’s ability to amend that part of the statute.

“This interpretation of article II of the Constitution is consistent with the people’s precious right to exercise the initiative power. (See Legislature v. Eu (1991) 54 Cal.3d 492, 501, 286) It also comports with the Legislature’s ability to change statutory provisions outside the scope of the existing provisions voters plausibly had a purpose to supplant through an initiative. (See Methodist Hosp. of Sacramento v. Saylor (1971) 5 Cal.3d 685, 691) We therefore hold that where a statutory provision was only technically reenacted as part of other changes made by a voter initiative and the Legislature has retained the power to amend the provision through the ordinary legislative process, the provision cannot fairly be considered “expressly included in ․ a ballot measure” within the meaning of Government Code section 17556, subdivision (f).”

These two Supreme Court decisions provide valuable guidance regarding the extent to which the Legislature can amend a voter-approved statutory initiative. Technical amendments and amendments that do not undermine the intent or purpose of the initiative are permissible. However, legislative amendments that will thwart the statutory initiative’s intent or purpose are not going to be judicially approved.

- Court-ordered Child Support - January 6, 2026

- Third-party Claims - January 6, 2026

- New Trials in California - January 5, 2026