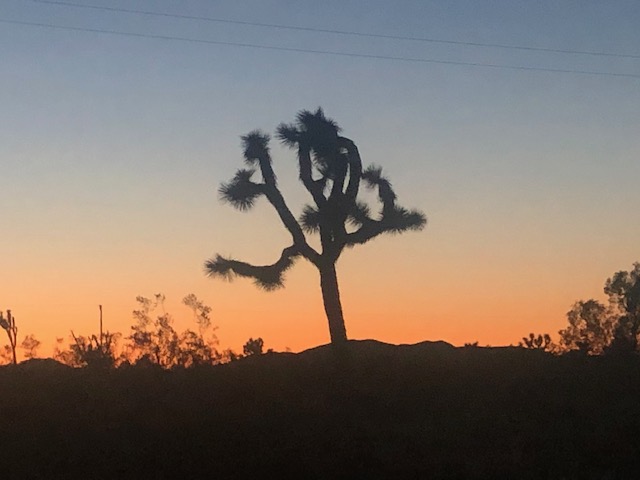

Joshua trees in Joshua Tree National Park. (Photo: Evan Symon for California Globe)

Joshua Tree Endangered Species Listing at a Stalemate

The battle is between the push for development and those fighting for preservation

By Laura Hauther, July 6, 2022 10:05 am

The Joshua tree may be the tourist-attracting symbol of America’s southwest deserts but since the petition to protect the western Joshua tree under California’s Endangered Species Act hit the desk of the Fish and Game Commission, it’s also become a symbol of the battle between the push for development and those fighting for preservation.

Brandon Cummings, Conservation Director of the Center for Biological Diversity created the petition at the heart of the controversy that was persuasive enough to convince the California Fish and Game Commission to give the western Joshua tree temporary protected status under California’s Endangered Species Act (CESA) as threatened in September of 2020.

The Fish and Game Commissions vote earlier this month was supposed to give the final thumbs up or down on the permanent listing but stakeholders on both sides of the issue rallied their troops, inundating the commission during the public comment period.

Petitions requesting protection can ask for either a threatened or endangered designation under the California Endangered Species Act. Species listed as threatened are less stringent protections.

Those wishing to see the protections made permanent were dealt a blow in April when the California Department of Fish and Wildlife recommended against the listing earlier this year, disagreeing with the petitioner’s conclusion about the impact of climate change on the range and number of the western Joshua tree.

Cameron Barrows, an retired ecologist from the Center for Conservation Biology vehemently disagrees with those conclusions. During a talk at the Mojave Desert Land Trust, Barrows argued that “(western Joshua trees) are no longer able to reproduce through much of their range. Many studies have confirmed this finding.”

Barrows said his own study focused on Joshua Tree National Park in 2013 found little new growth in over half of their habitat in the park.

Opponents of the permanent listing argue that stopping the construction of large solar fields in desert areas populated with western Joshua trees would have a negative effect on the development of green energy options.

After the temporary protections were put in place, The Fish and Game Commission signaled their willingness to compromise by giving the go ahead to fifteen solar projects in Kern and San Bernardino Counties. They were granted exemptions because California Environmental Quality Act reviews had already been done and the commissioners weighed the benefits of renewable power in the wake of climate change.

The sole vote against allowing the solar projects to go forward was commission President Samantha Murray, saying she did not want to create a bureaucratic backdoor with such emergency exemptions allowing the removal of the trees based on economic factors.

On June 15, what was supposed to be the final vote to decide if the listing would go ahead, battle lines were drawn resulting in a stalemate, and eventually ending in a compromise decision after eight hours of comments and deliberation. The deadlocked California Fish and Game Commission decided to put off the final decision on the listing until their next meeting in October.

In a Calmatters editorial, Brandon Cummings called out the Department of Fish and Wildlife’s report recommending against the listing for ignoring the effects of climate change – like worsening drought, the increasing number and severity of wildfires and rising temperatures – that are generally accepted throughout much of the scientific community.

Cummings points to specific incidents, like wildfires in 2005 and the devastating Cima Dome fire in 2020 that burned over a million Joshua trees. Dry conditions, high temperatures and the growth of invasive grasses created a perfect storm of conditions leading to the massive loss.

Despite not recommending listing, the Department of Fish and Wildlife’s review of several studies acknowledges that “habitat loss continues to be a substantial, ongoing threat” and “a large proportion of the western Joshua tree’s habitat …occurs on private land that is vulnerable to continuing modification and destruction.” The study concludes there is enough protected land and the population of trees is large enough to offset the danger of extinction in much of its range by the end of the 21st century.

Many arguments against the listing emphasize the roadblocks it would create for housing and solar field development, rather than providing data to back up the claim that climate change is happening too slowly to impact the trees.

Chrisina Sanchez, a desert ecologist with Every Leaf Speaks said she was shocked to see what she considers a deceptive map of the Joshua tree current range on private and protected land during San Bernardino Supervisor Dawn Rowe’s presentation at the hearing. That map included the range of both the western and eastern Joshua tree, giving an impression of a much healthier outlook for the western Joshua tree.

“She was comparing private versus public where the Joshua tree occurs…but the map included…the Mojave National Preserve, that’s not where the western Joshua tree occurs, it’s not within that range.”

Joining San Bernardino County in opposition to the listing are many high desert cities and construction, large solar field developers and realtor’s trade groups.

Cities like Victorville are experiencing double digit growth as the pressure for more housing pushes development throughout Southern California. They argue the protections already in place are enough to mitigate impact on the trees survival without holding back growth and development.

Even though Joshua trees are notoriously difficult to successfully relocate, they claim 119 western Joshua trees were successfully moved to a city owned golf course to make room for a 360 acre solar power plant, according to the Desert Sun.

Despite not recommending listing, the Department of Fish and Wildlife’s review of several studies acknowledges that “habitat loss continues to be a substantial, ongoing threat” and “a large proportion of the western Joshua tree’s habitat … occurs on private land that is vulnerable to continuing modification and destruction.” The study concludes there is enough protected land and the population of trees is large enough to offset the danger of extinction in much of its range by the end of the 21st century.

Once it was clear the commissioners were at a stalemate and the final decision would be delayed they asked Chuck Bohnam, the director of the Department of Fish and Wildlife, to look into the possibility of a conservation plan for the western Joshua tree that would incorporate input from conservationist and stakeholders opposing the listing.

Conservation plans take years to develop but the Fish and Game Commission might use this as a way to strike a compromise between the two opposing forces.

One thought on “Joshua Tree Endangered Species Listing at a Stalemate”