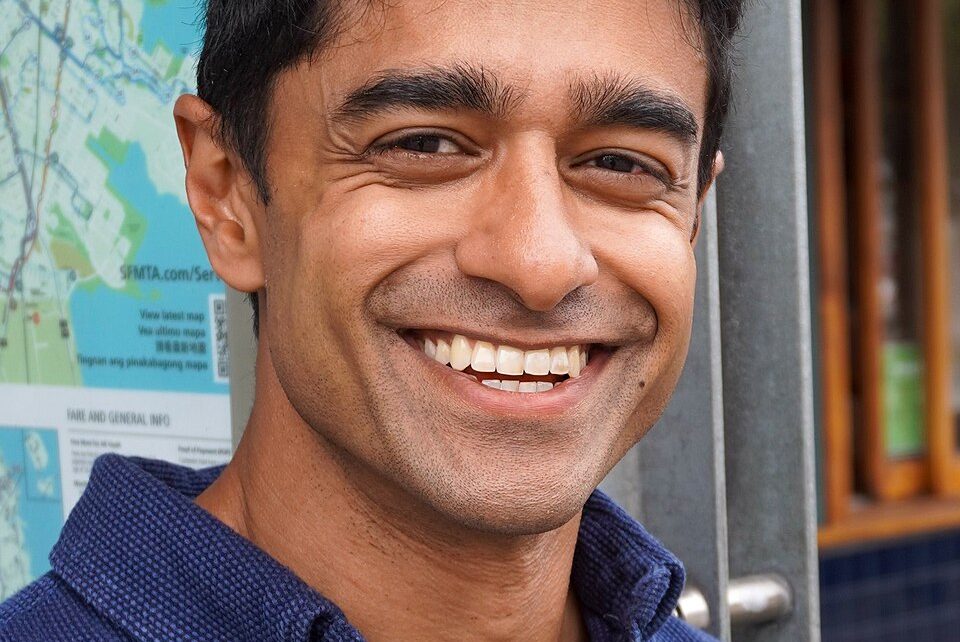

Saikat Chakrabarti at a Muni stop in San Francisco. (Photo: Saikat Chakrabarti media kit)

Seize PG&E? A Congressional Candidate Makes the Case

Saikat Chakrabarti wrongly thinks he can grab control of the utility

By Richie Greenberg, December 31, 2025 2:30 pm

In progressive activism, few ideas capture the imagination quite like the concept of seizing control of essential services from private corporate hands and placing them under government oversight. And that’s just what a candidate for Congress suggests.

Saikat Chakrabarti, a former chief of staff to Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and now a congressional candidate for San Francisco, running to succeed Nancy Pelosi, recently took to Twitter/X to proclaim that the city could simply “use eminent domain to seize PG&E’s infrastructure now and switch to public power.”

San Francisco could use eminent domain to seize PG&E's infrastructure now and switch to public power. We don't need new legislation to do this, all we need is political will. pic.twitter.com/rs8GzS923r

— Saikat Chakrabarti for Congress (@saikatc) December 29, 2025

He insisted, “We don’t need new legislation to do this, all we need is political will.” FYI, he’s the acknowledged far-left congressional candidate, a socialist basically, running on Medicare for all, a transition to green energy and to stop funding the “genocide in Gaza.” He’s a deci-millionaire, making his fortune in Tech. Big surprise.

Chakrabarti’s proposal rests on a fundamental misunderstanding (or perhaps a deliberate glossing over) of what eminent domain truly entails. Eminent domain is not a magic wand for “seizing” private assets free of cost or consequence; it’s a constitutional power that demands fair compensation under the Fifth Amendment. Far from being a cost-free takeover, any attempt by San Francisco to acquire PG&E’s electric energy distribution network would require the city to pay fair market value, a figure that easily balloons into the billions. Eminent domain isn’t confiscation; it’s a forced sale at a price determined through rigorous valuation, often contested in court. What he proposes is a dangerous expansion of government authority, where taxpayer dollars are funneled to prop up public monopolies at the expense of private innovation. PG&E, despite its flaws, operates in a regulated energy market where competition and accountability drive improvements, something a city-run utility, insulated from market pressures, would lack.

The acquisition costs alone are staggering, underscoring the fiscal illiteracy embedded in Chakrabarti’s tweet.

San Francisco has already floated offers around $2.5 billion for PG&E’s local assets, including wires, poles, substations, and meters serving roughly 472,000 customers. But PG&E has rebuffed the offers as undervaluations, and independent assessments suggest the true cost could climb to nearly $3 billion or more, especially when factoring in severance damages for the impact on PG&E’s broader operations. Billions may be required when including financing through revenue bonds, which would saddle local ratepayers with decades of debt service payments.

This isn’t mere pocket change; it’s a monumental financial commitment that diverts resources from core city priorities like public safety and infrastructure maintenance. Imagine the outrage if a private company proposed such an expenditure without clear returns, yet radical progressives like Chakrabarti pooh-pooh it away as mere “political will.” In reality, this would likely translate to higher utility bills or tax hikes, burdening working families in a city already grappling with exorbitant living costs.

Beyond the upfront purchase price, the costs to integrate PG&E’s operations are mind-boggling, revealing the naive optimism of Chakrabarti’s vision. Transitioning to a municipal-owned utility wouldn’t happen overnight; it would involve absorbing hundreds if not thousands of PG&E employees, aligning pensions and benefits, and assuming liability for ongoing maintenance of an aging grid. PG&E’s resistance has already generated over 130 legal filings in the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) process, initiated in 2021, with delays adding at least $35 million to the city’s tab since 2018. Litigation could drag on for years, as PG&E contests valuations and argues that a breakup harms statewide reliability and wildfire mitigation efforts. Government entities are notoriously inefficient at such integrations, look no further than San Francisco’s own track record with projects like the Central Subway, which ballooned from $647 million to over $1.6 billion due to mismanagement.

Moreover, ongoing operational costs would exacerbate the fiscal nightmare. Running a public utility means the city would shoulder billions in annual expenses for maintenance, upgrades, and emergency responses without the profit incentives that drive private efficiencies. PG&E’s statewide operations cost billions yearly, and San Francisco’s dense urban grid, while potentially less expensive per capita than rural areas, still requires massive investments to address deferred maintenance and modernize systems like SCADA (an industrial control and monitoring system) and metering. Critics from labor unions like IBEW 1245 have warned that such a takeover “would hurt almost everyone and would improve nothing,” citing risks to jobs, service quality, and affordability. This epitomizes the pitfalls of public ownership: without market discipline, costs spiral as bureaucrats prioritize political agendas over operational excellence. Proponents claim long-term savings from eliminating PG&E’s profit margins, but historical voter rejections of similar measures in 2008 highlight public skepticism over these “savings” materializing amid government bloat.

Chakrabarti’s oversimplification ignores these realities, framing the issue as a simple battle against “corporate greed” rather than a complex economic equation. True reform lies in bolstering private accountability through deregulation and competition, not expanding government control. PG&E’s monopoly status is a product of overregulation, and breaking it via eminent domain would merely replace one monopoly with another: city hall’s. The recent blackouts in December 2025 have fueled calls for action, but rushing into a multi-billion-dollar gamble risks fiscal disaster. Progressives despise PG&E for ideological reasons, viewing it as a symbol of capitalist excess, but we see the utility’s challenges as opportunities for market-driven fixes, not state seizures.

Public utilities elsewhere, while sometimes cheaper, often rely on subsidies that mask true costs, something San Francisco, with its budget deficits, can ill afford. Chakrabarti’s claim reduces this to “political will,” but we know that will without wisdom leads to waste.

- Greenberg: Yes, Trump Has the Legal Power to Strike - March 2, 2026

- Greenberg: Newsom Once Again Proves He’s Unfit to Lead - February 26, 2026

- Greenberg: The Irony – Ineligible Blacks May Fund SF Reparations - February 22, 2026

Communism in SF. Sure that will work out well, especially with DEI hires over merit. It will be expensive. More people fleeing the city.

Will these progressive communist democrats ever stop Breaking stuff. They have broken San FranFreakshow. Now they want to break PG&E ( not a fan of PG&E anyway) and Go without lights. Maybe we ought to let them. American Democrat commies are children that have the right to vote. Unfortunately.

“Saikat Chakrabarti, a former chief of staff to Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and now a congressional candidate for San Francisco”

This guy looks like a deer in the headlights. There is not a lot of critical thinking going on up there.

PG&E is jacked up enough as it is, from being packed with idiocies in it’s construction standards, malevolent “inspectors” and management not overburdened with brains. However, think of a utility ran by the DMV partnered with CARB with all the public welfare concern and political activism of the SEIU. Think of the Jerry Brown/Newsom train to nowhere, consider the LADWP – held together with bandaids and electrical tape – shutting off power to customers for political reasons like they did during the covid episode. And wasn’t a DSA operative named Saikat Chakrabati the campaign manager that propelled Alexandria Ocasio Cortez to a seat in the US Senate? No frickin bueno.

I read the article and posted in a rush because I had somewhere to be. The bit about AOC and the senate was a brain fart, she’s in the house.

Richie,

we have two good Repub. candidates running for the governor position: sherif Chad Bianco and Steve Hilton. What if instead of competing against each other, one will run for governorship and the other for Congress. I believe they both will have good chances. Is this a very crazy suggestion? because we can’t have any of these awful creatures.

can we ask