California’s Top Two Primary System Still A Focus Of Debate

Goals remain inconclusive, and perils persist

By Cliston Brown, June 11, 2018 9:18 am

In 2010, California voters passed Proposition 14, approving sweeping change to the state’s primary elections. This did away with party primaries and replaced them with an “open primary” featuring candidates of all parties. Starting in 2012, the top two primary finishers for statewide office, Congressional seats, and state legislative seats have all advanced to the November general election, regardless of party.

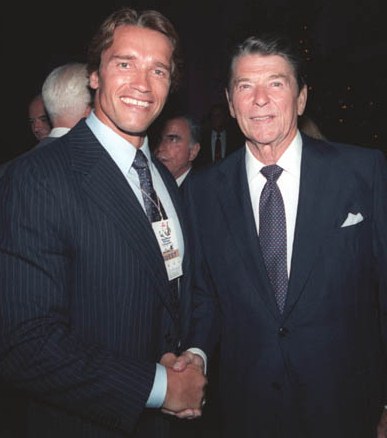

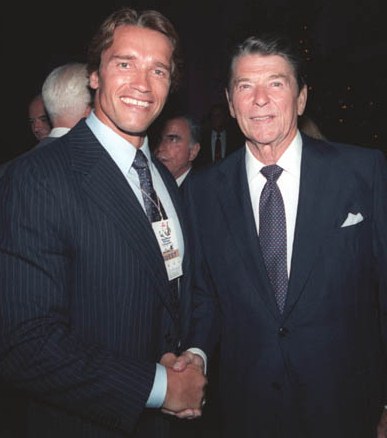

Supporters of the new system, led by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger (R), thought that the new system would dilute partisanship by forcing candidates of all parties to appeal to a broader range of voters. The theory was that low-turnout primaries favored more extreme left or extreme right candidates in the Democratic and Republican intramural contests, respectively. But an open—and wider—choice by all voters would, in theory, produce winners who were less ideological and more open to compromise, and proponents thought this might not just produce more comity, but also increase turnout.

When it comes to turnout, the theory has proven incorrect. In fact, the 2014 midterm elections in California featured the lowest turnout ever recorded in the state: 25% in the primaries and 42% in the general election. According to the San Francisco-based Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC), these numbers were down 8% in the primaries and 13% during the general election as compared to the previous midterms in 2010, the last ones conducted under the traditional system. While California is still counting votes after the recent June 5 primary, it does appear that this year will not set new records for low turnout.

Eric McGhee, a PPIC research fellow, says the results of the top-two system have been a mixed bag. Clearly, the new system has given the voters more choices, at least at the primary stage, but there is not yet much evidence that the other goals—more turnout and more bipartisanship—have developed.

“It has certainly given voters more choices on average,” McGhee told California Globe. “They can pick any candidate they like in the primary stage, and there is often a competitive same-party fall contest in districts that are otherwise dominated by one party. It has not really increased turnout, though there are no signs that it has decreased turnout either. In same-party contests, ‘orphaned’ partisans (members of a party that is not represented on the ballot) will often skip a same-party contest, but they will still vote for other races.”

Whether the moderating effect has taken place is harder to quantify. McGhee says his joint research with colleague Boris Shor, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Houston, has shown some slight moderating by state-level Democrats.

“We found that the Democratic caucus in the legislature has been a little more moderate under the reform, though one can attribute at least some of that change to two other reforms implemented at the same time (redistricting commission and relaxed term limits),” McGhee said. “There is no sign yet that Democrats in the congressional delegation, or any elected Republicans, have become more moderate.”

Another largely unanticipated bit of fallout from the new system is the prospect that one party or the other might get shut out of the fall election in races it otherwise might have had an excellent chance to win. This happened in 2012, when a Republican-held U.S. House district considered vulnerable to a Democratic takeover saw two Republicans advance to the general election because too many Democrats divided the left-leaning vote.

National Democrats, sanguine for a chance to retake the U.S. House this year and eyeing at least seven Republican-held districts in California as part of their strategy to net the 23 seats they need, were worried that they might lose out on two or three Golden State opportunities due to the top-two system.

As of this article’s submission, Democrats appear to have avoided this sorry fate, though as of now, there are still many votes to be counted and a couple of Democratic runners-up have little room to spare.

Republicans, however, dodged this bullet as well, qualifying candidates for most of the top statewide races. GOP strategists had been concerned that if they were shut out of both the U.S. Senate and gubernatorial races, it would depress Republican turnout in the general election and take several of their vulnerable Congressmen down to defeat. Republicans qualified for every statewide race except the low-profile lieutenant governor’s race and the U.S. Senate race, where longtime Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein is a heavy favorite to defeat fellow Democrat Kevin DeLeon, the former State Senate president pro tempore, in November.

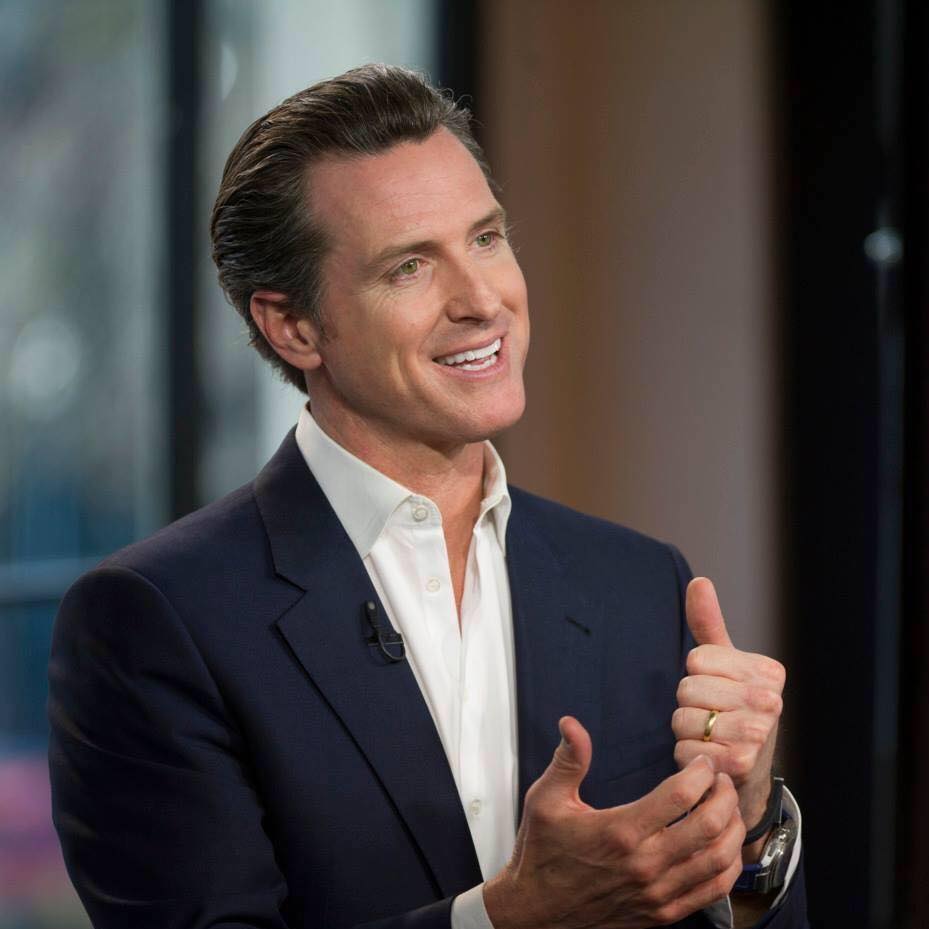

But by getting businessman John Cox into the top two in the governor’s race—closing strong to handily beat out former Los Angeles mayor Antonio Villaraigosa (D) for second place—Republicans avoided their worst fears. Cox is a heavy underdog against Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) in the fall election, but at least Republican voters have a big-ticket race to entice them to the polls in November.

In short, California’s unusual system presents some unusual challenges, and whether it has achieved what the voters hoped it would remains up for debate. But given that the voters put this system in place, it seems unlikely that it is going away unless something drastic happens—say, for example, California’s dominant Democrats getting shut out of a high-profile Senate or governor’s race. In that case, one of the nation’s most progressive states might develop a case of buyer’s remorse. But only time will tell.

Cliston Brown is a communications and government relations executive and political analyst in the San Francisco Bay Area who previously served as director of communications to a longtime Democratic Representative in Washington, D.C. Follow him on Twitter and visit his website.

- California’s Top Two Primary System Still A Focus Of Debate - June 11, 2018

- Voters’ Second or Third Choices Likely to Determine New SF Mayor - May 22, 2018

Yeah that’s what I’m talking about babyn–ice work!