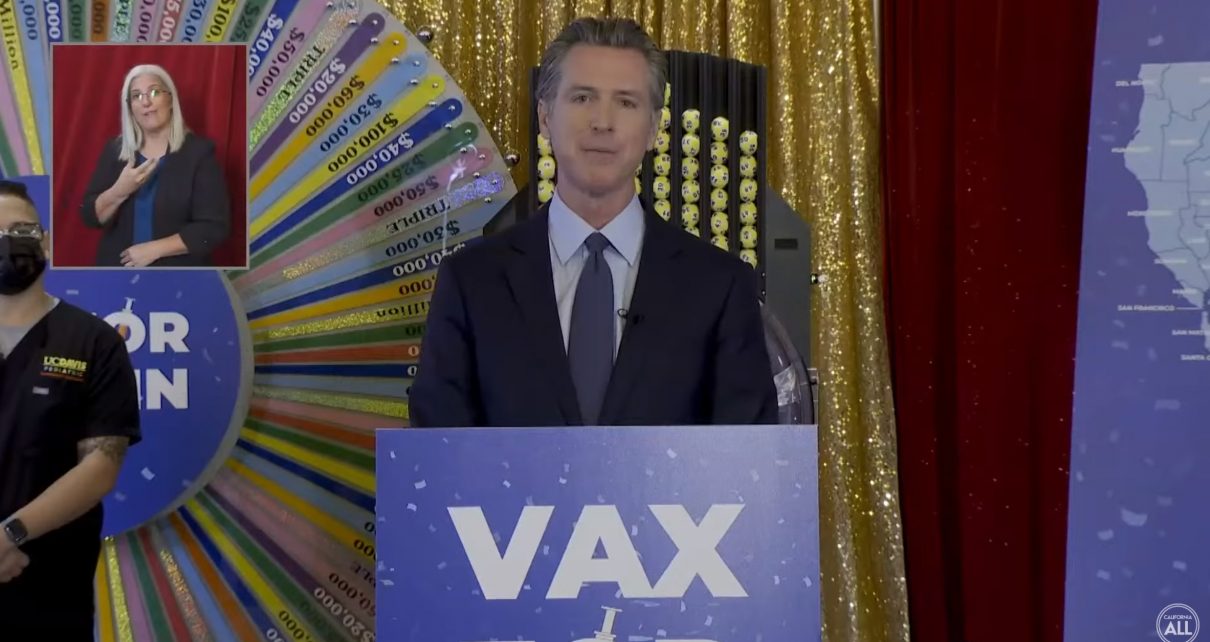

Governor Gavin Newsom "Vax for the Win" lottery drawing. (Photo: gov.ca.gov)

As the United States Leaves the WHO, Newsom Grandstands

A leader willing to bypass democratic accountability at home while posturing as a sovereign actor abroad is not offering leadership—but issuing a warning

By Rita Barnett-Rose, January 27, 2026 9:02 am

On January 22, 2026, the United States formally completed its withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO), citing the organization’s mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic, its failure to enact meaningful reforms, and its lack of institutional independence.

That same day—after meeting privately in Davos, Switzerland, with WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus—California Governor Gavin Newsom announced that California would become the first U.S. state to “join” a WHO-affiliated network, the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN). He framed the move as a “counterweight” to what he called the Trump administration’s “reckless” decision to leave the WHO.

Fortunately, Newsom has no authority to bind California—or Californians—to the WHO. California is not a sovereign nation, and its governor cannot conduct foreign policy.

But that does not end the inquiry.

By aligning California with a WHO-coordinated network immediately after a federal withdrawal, Newsom has raised serious legal and sovereignty concerns. Even without treaty power, the move signals continued alignment with an international health apparatus the United States has rejected and invites scrutiny over data sharing and the limits of state authority.

Why the United States Left the WHO—and Why Newsom’s Response Matters

The decision to leave the WHO was neither sudden nor unexplained. In July 2020, during his first term, President Donald Trump issued a notice of withdrawal in response to the organization’s handling of COVID and what he viewed as an unfair funding burden on U.S. taxpayers. That withdrawal was reversed by the Biden administration in early 2021, keeping the United States inside the WHO as flawed COVID policies and top-down coercion continued.

After returning to office in January 2025, President Trump renewed the withdrawal, triggering the required one-year notice period under the WHO Constitution. In January 2026, the withdrawal became final.

In announcing the decision, Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Secretary of State Marco Rubio cited the WHO’s COVID-era failures and actions that repeatedly ran contrary to U.S. interests and harmed the American public. They also referenced earlier concerns about proposed expansions of WHO authority—including the pandemic agreement and amendments to the International Health Regulations—which would have normalized emergency powers, shifted authority away from national governments, and created compliance pressure even when guidance was formally non-binding.

Structural conflicts compounded those concerns. A significant portion of the WHO’s budget now comes from voluntary, earmarked contributions by NGOs and private organizations deeply invested in vaccine development and deployment—including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and GAVI—giving non-sovereign actors outsized influence over global health priorities despite having no electoral accountability.

Withdrawal from the WHO does not mean abandoning global disease monitoring. HHS has stated that the United States intends to pursue targeted bilateral and multilateral data-sharing arrangements that preserve cooperation without ceding emergency authority to a centralized global body.

These concerns over global and NGO control mirror what many Americans experienced during COVID. Distrust of the WHO hardened not because it failed to act aggressively enough, but because it actively pushed global, compliance-driven pandemic governance—mandates, population-wide restrictions, and one-size-fits-all interventions that discounted natural immunity, risk stratification, and legitimate scientific disagreement, with disastrous global consequences.

Yet despite that backlash, Newsom announced California’s alignment with the same international framework from Davos, explicitly framing the move as opposition to federal policy.

The Hard Constitutional Limit: What Newsom Can—and Cannot—Do

There are clear limits on Newsom’s unilateral actions. Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution prohibits states from entering treaties or alliances, and states lack authority to conduct foreign policy. Those powers belong exclusively to the federal government.

Newsom therefore cannot commit California to WHO treaties, subject Californians to WHO emergency declarations, enforce WHO mandates, or override the federal government’s withdrawal. Whatever his rhetoric suggests, he lacks the authority to “join the WHO.”

What Newsom actually announced was California’s participation in GOARN, a WHO-coordinated technical network intended to facilitate disease surveillance and response planning. GOARN does not impose mandates or create binding legal obligations, and participation alone does not subject Californians to WHO authority. Any meaningful funding commitment by California would also require legislative approval, underscoring that Newsom’s announcement was political signaling rather than authorized state policy.

Nevertheless, California’s decision to deepen alignment in the wake of federal withdrawal raises unresolved questions about sovereignty, data sharing, and the proper limits of state authority.

Legal and Sovereignty Concerns

When a governor frames international alignment as opposition to federal foreign policy, even nominally voluntary participation becomes constitutionally fraught. States may engage in limited international activity, but they may not undermine national policy coherence or present themselves as alternative diplomatic actors. Newsom’s framing therefore invites scrutiny under the foreign-affairs preemption doctrine, which is triggered when state action or rhetoric intrudes upon the federal government’s exclusive authority to conduct foreign policy.

Although framed as voluntary, announcing the move from Davos, immediately after U.S. withdrawal, and explicitly as a “counterweight” to federal policy signals an effort to treat California as a sovereign actor rather than one state within the Union.

Data sharing raises additional concerns. While privacy laws remain in force, COVID demonstrated that data pipelines matter. Even aggregated and de-identified data can shape modeling assumptions, risk frameworks, and downstream policy decisions. The issue is not that GOARN can impose mandates, but that California’s voluntary sharing of public-health data with a WHO-coordinated network allows foreign-aligned frameworks—already associated with pandemic-era coercion—to influence California Department of Public Health policy in ways that may later be used against Californians.

Newsom’s Record and Motive

Newsom’s motivation here is obvious. As a term-limited governor with presidential ambitions, he cannot plausibly run on his record in California. That record includes a worsening homelessness crisis, rising crime, fraud scandals near his inner circle, wildfire mismanagement, and tens of billions lost to pandemic-era unemployment fraud.

Faced with these realities, Newsom’s most reliable strategy has been to cast himself as the anti-Trump—reflexively opposing federal policy and marketing himself as a symbolic counterweight rather than a competent executive. The GOARN announcement fits that pattern. It is not governance; it is branding.

But this move is not only about opposing Trump. It reflects a deeper ideological alignment. Newsom’s COVID leadership in California was defined by rule through executive order, aggressive mandates, suspended safeguards, and prolonged emergency authority with no clear endpoint. That governing style closely mirrored the WHO’s centralized, one-size-fits-all pandemic framework—far more than the approach taken by most U.S. governors. The United States has now rejected that model. Newsom has not.

Seen in that light, Newsom’s appearance at Davos is no accident. Davos is where global elites and international institutions signal priorities and reward ideological alignment, not where U.S. governors advance state interests. Announcing California’s GOARN participation from Davos—after a private meeting with the WHO’s Director-General—reads as a deliberate signal: Newsom is fluent in, and aligned with, the top-down technocratic governance model the WHO sought to entrench during COVID, and he is willing to carry it forward should the opportunity arise.

Newsom Can’t Bind California—but He Can Still Cause Damage

The United States’ withdrawal from the WHO reflects a hard-earned lesson: unelected global health bodies, heavily influenced by NGO funders, should not dictate sweeping policies insulated from democratic control. While Gavin Newsom cannot legally bind Californians to WHO authority, his decision to affiliate the state with GOARN is nonetheless troubling and constitutionally suspect.

Newsom’s term ends in 2027. Californians cannot bring it to a close soon enough. The rest of the country should take note: a leader willing to bypass democratic accountability at home while posturing as a sovereign actor abroad is not offering leadership—but issuing a warning.

- As the United States Leaves the WHO, Newsom Grandstands - January 27, 2026

- How California Eliminated Medical Exemptions by Design—and Why Hepatitis B Will Expose the Lie - January 22, 2026

- Jurisdictional Science and the Collapse of Medical Legitimacy - January 17, 2026

As Rita Barnett-Rose pointed out, Gov. Gavin “Hair-gel Hitler” Newsom attempt to affiliate California with GOARN is deeply troubling and suspect but it’s not surprising considering that he’s a WEF globalist stooge who acts like a petty dictator. Even after he leaves office, no doubt the next Democrat who is installed with voter fraud as California’s governor will continue the Democrat’s lawless destruction of the Constitution?