Tahoe, An Ode

As the Caldor fire rages, an English professor considers the loss

By Royce Kallerud, August 31, 2021 7:16 pm

California born, and raised in the Midwest, Lake Tahoe drew me in before I could know. My second visit was part of a cross-country train trip with my future wife that had us leaving Los Angeles hours before the Northridge earthquake, stuck in Chicago when our train froze to the tracks, barely making it home before food poisoning laid us low.

My first visit was with my recently divorced dad, my older sister, my younger brother, and my recently divorced older brother Larry who brought with him a card dealer friend who said his name was Ray. We skied by day, played blackjack through the nights (with me unaccountably winning like a boss) and, as it all was wrapping up, watched Larry and Ray nearly pilot their plane into a mountainside. Now that mountainside is on fire.

To me Tahoe first seemed more Niagara Falls than Yosemite. Gamble, drink, ski. I didn’t recognize the beauty because it was too strange, and too much. Maybe if Lake Tahoe had been a national park I would’ve known how to feel. But over decades I became sure that Mark Twain was never more right than when he called Lake Tahoe “the fairest picture the whole earth affords.”

The British Romantics called nature sublime when it exceeds our senses. As much as we need to, we literally can’t see the whole mountain, what’s beyond the horizon, or what’s at the bottom of the lake. Maybe though we can get closer if we remember that the sublime has its root in barely tamed and carefully hidden fears. Before the Romantics, Europeans saw the mountains as scars on the landscape, barriers to commerce and, most of all, terrifying, an awareness always just below the surface in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

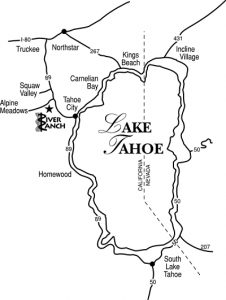

So far as I know, the Romantics didn’t literally write about wildfires. But they left notice that as much as we think we’ve tamed nature, it tells us otherwise. Tahoe’s Martis Fire started on my wedding day and several of our guests barely made their flights. My wife and I headed south to honeymoon at Yosemite, never noticing the flames. Last month the Beckwourth Complex Fire closed the highway as we drove to see my dad at the hospital in Reno, sending us on a long detour. A few days later we watched the glow of the Tamarack Fire from the safety of Tahoe’s magical west shore.

I recently learned that we likely would have had a Lake Tahoe National Park if it weren’t for tourism, logging, and mining. That it’s not a national park though is apt, especially now: All these forces—commerce, violence, hedonism, reverence—are part of this lake. Most of all, as with the official national parks, our love of these places can’t be separated from the brutal history of Native dispossession. Of course Lake Tahoe was Fredo Corleone’s last stop.

It’s hard not to see all of these as missed portents, even as none of it comes close to subduing the wonder I feel every time I open my eyes to this lake. To miss what’s at the end of one’s nose is to be human, and alive. But the sublime might also show us how to recognize what we most need to, to still love the world but not keep missing the signs that we’re burning it down. Which all makes my decades with Lake Tahoe not only inseparable from my family and marriage, but its own lifelong romance.

The title of this story is homage to the poem “California, An Ode” by Barbara Gibbs.

- Tahoe, An Ode - August 31, 2021

Beautiful reflection, Royce! It’s so true that what we most need is “to still love the world but not keep missing the signs that we’re burning it down”.

When you refer to wedding guests almost missing flights, you may recall that Jackie, baby Zoë and I spent a few days in Truckee afterward, biking along the river with Zoë in tow. But to get there we unknowingly drove dangerously close to a fire and embers were lighting along the road, which was closed soon after we made it through.