California new home development. (Photo: Katy Grimes for California Globe)

How Do You Solve a Problem Like CEQA? Part One

Environmentalism run amok is destroying economic opportunities for all Californians, and CEQA is the beating heart of the beast

By Edward Ring, June 14, 2023 2:45 am

Part One – How CEQA Has Made California Unaffordable

The following is the first of a three part series on the impact of the California Environmental Quality Act on development in California and ways to potentially improve the law. It is written in response to hearings conducted over the past three months by the California’s Little Hoover Commission.

The California Environmental Quality Act, universally known by its serendipitously phonetic acronym “SEE-kwa,” was passed by the state legislature in 1971. At that time, it was the first legislation of its kind in the nation, if not the world. Its original intent was to “inform government decisionmakers and the public about the potential environmental effects of proposed activities and to prevent significant, avoidable environmental damage.”

Over the past half-century, however, CEQA has acquired layers of legislative updates and precedent setting court rulings, warping it into a beast that denies clarity to developers and derails projects. When projects do make it through the CEQA gauntlet, the price of passage adds punitive costs in time and money. Knowing this will happen deters countless investors and developers from even trying to complete a project in the state.

Starting earlier this year, California’s nonpartisan Little Hoover Commission began studying the impact of CEQA and soliciting suggestions from the public. They have held four public hearings so far, on 3/16, 4/13, 4/27, and 5/11. The live hearings, lasting in total over 12 hours, in all four cases were attended by almost nobody apart from the commissioners and the people invited to testify. Altogether, so far on YouTube these four hearings have attracted just over 1,000 online views. Not much, considering CEQA’s impact.

Anyone who has waded through all 12 hours of these hearings may agree that certain themes came up again and again, and will doubtless factor significantly in determining what the commission ultimately recommends. The remainder of this report will summarize some of the recurrent or noteworthy observations and recommendations from these hearings, along with ideas solicited elsewhere from Californians that have had to deal with CEQA either as attorneys, judges, developers, or activists. To be clear, and in the interests of full disclosure, this report is not intended to offer a neutral perspective on CEQA. It is rather an attempt to further expose how problematic CEQA has become, and offer alternatives.

While CEQA is most often associated with housing, and is often cited as a major obstacle to building more housing in California, it affects any project that has potential environmental impacts. Along with housing development, this includes commercial development, sports facilities, and all types of infrastructure including dams, aqueducts, wastewater treatment plants, desalination plants, power plants, power transmission lines, pipelines, ports and port upgrades, rail, road, mines, quarries, logging, land management; anything that changes land use and may cause “significant” environmental damage. And in every case, the influence of CEQA has its champions and its detractors.

What may inform CEQA judgments has changed over the decades. In one of the first of the Little Hoover Commission’s hearings, a panelist informed the group, speaking with almost reverent certainty, that five of California’s major airports “would be underwater by 2050.” Such remarks and sentiments now pervade CEQA proceedings. Climate change impact, which was absent from CEQA cases in the 1970s, has become one of the dominant concerns brought in CEQA cases today.

The Labyrinth Called CEQA

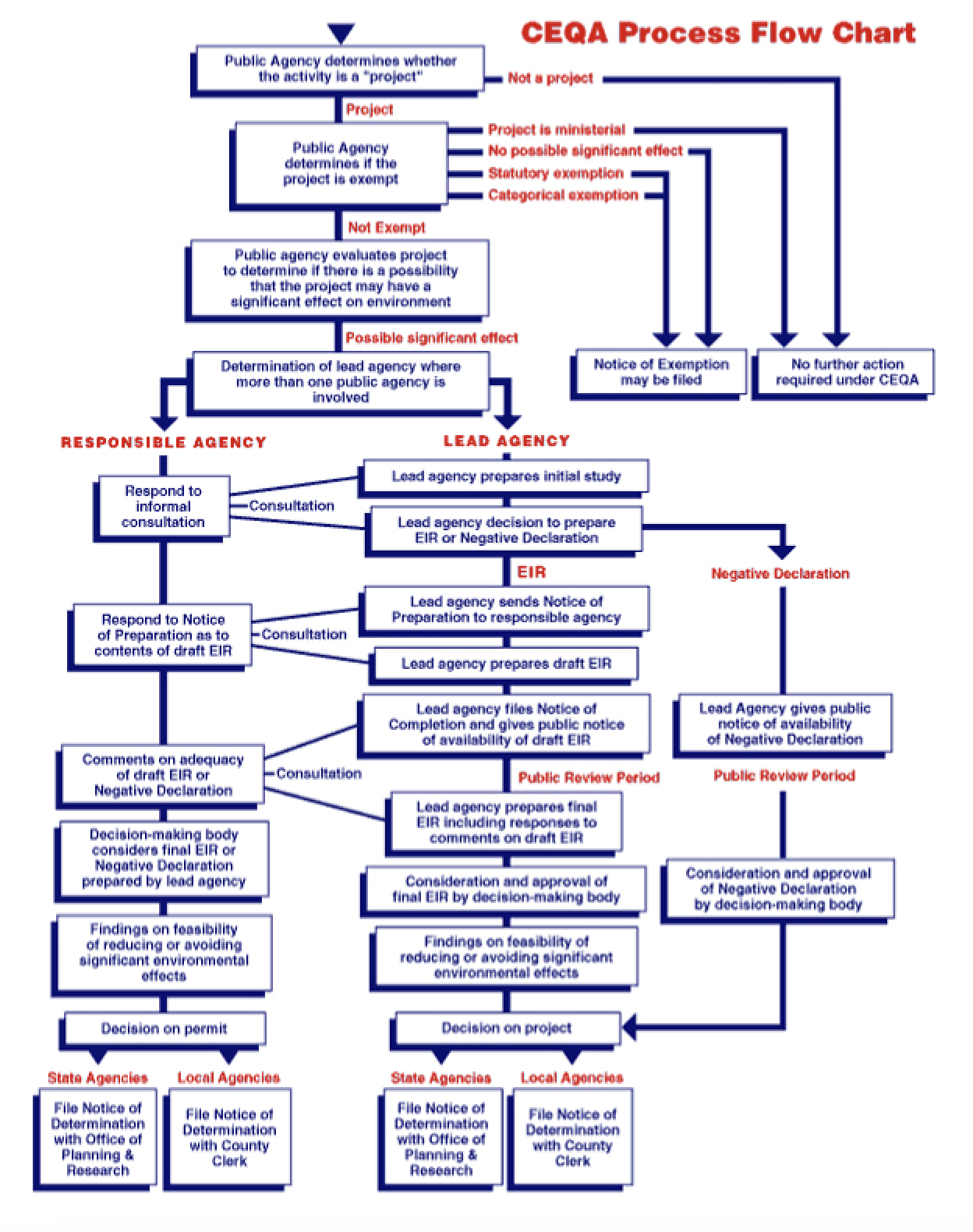

The concept of CEQA is unassailable. If a project may cause “significant impact” to the environment, the CEQA process will ensure that either the impact is appropriately mitigated, or the project is stopped. The chart depicted below, courtesy of the California Department of Conservation, depicts the CEQA process. If anything, this elaborate flow chart understates what a project developer is up against thanks to CEQA. There is rarely just one “responsible agency.” If any of these agencies determine there are any flaws or omissions in the required “Environmental Impact Report” (EIR), the process often has to be restarted. The delays between inter-agency responses can consume months if not years. The “public review period” leaves room for a 3rd party to file a time consuming lawsuit right up to the last minute before a project is finally approved.

If the complexity of CEQA as depicted in this flowchart makes obvious the difficulties facing anyone who develops property or manages land, it also explains why exemptions have become the shortcut taken for politically favored projects. Exemption from CEQA has been the default remedy pursued by the state legislature whenever they decide it is important to prioritize any project, or category of projects. But carving out one exemption after another does not fix CEQA. Even if the state legislature were capable of correctly prioritizing projects, which is an absurd reach, it remains an absolute process without gradation. Anointed projects skip through the exemption portal and are fast-tracked, even though many of them may cause environmental impacts that are significant. Meanwhile, all other projects, many of which are just as urgently required, must go through the labyrinth called CEQA.

Would True Environmental Justice Include More “Greenfield” Development?

Along with the relatively new and central role of climate change impact in the CEQA process, another major new concern now considered in CEQA cases is “environmental justice,” that is, the alleged disproportionate effect development projects may have in low income neighborhoods. This allegation is not unfounded, although the causes predictably attributed to this – a legacy of systemic racism – are more nuanced than conventional wisdom may acknowledge. Residential areas that are situated in close proximity to a network of freeways, industrial parks, airports, seaports, and warehouse districts, for example, are going to have more noise and more air pollution than residential areas that are in the foothills peripheral to a major urban center. Homes and apartment rentals in less desirable neighborhoods will be more affordable, so it is natural that on average, residents with lower household incomes will be living there. Campaigns for environmental justice can be based solely on economics without sacrificing credibility or moral worth.

Regardless of the underlying causes, it is valid to argue that yet another industrial project in a neighborhood that already has a high density of industrial development is going to add its incremental contribution of noise and pollution to a place already saturated with noise and pollution, whereas putting that same project in a pristine affluent suburb will not. It is also valid to argue that the residents and elected officials in wealthy neighborhoods have the economic wherewithal to hire attorneys to litigate against industrial projects and high density housing in their neighborhoods, whereas these same projects can be directed into lower income neighborhoods where the residents do not have the resources to resist.

This gives rise to a criticism of CEQA that is double edged. On one hand, CEQA offers people in low income communities one of the only legal tools available to fight high density housing and industrial or warehouse development that will create more noise, more congestion, more of a service burden, and more pollution in their communities. But at the same time, while residents in these low income communities have to find an attorney willing to carry their objections, often pro bono, into a legal battle, CEQA is an off-the-shelf, potent weapon in the hands of wealthy residents across town, who deploy it at will to keep high density housing and unwanted commercial development out of their communities.

One solution to this conundrum which some would consider a win-win would be to develop entire new cities on open land in California. Doing this would preserve the ambiance of existing neighborhoods, regardless of their average household income, and might even facilitate de-densification. It would lower the price of housing everywhere, making it easier for low-income residents to afford to either improve their neighborhoods or migrate to new communities. Doing this, however, would require massive state investment in enabling energy, water, and transportation infrastructure. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, building enabling infrastructure was something the state made a budget priority and performed remarkably well. Today, California’s state government has not made infrastructure investment a sufficient priority, and this failure to maintain and expand California’s infrastructure is frequently blamed on the roadblocks thrown up by CEQA.

Should densification and rationing be the only answer to environmentalist concerns? This question should be faced honestly. Is it impossible to construct new infrastructure to enable suburban growth? Why? California is a big state, with thousands of square miles of land that seems to be ripe for carpeting over with sprawling wind and solar farms, while new homes and new roads remain anathema. There’s room for both. California’s urban footprint consumes about 8,000 square miles, which is only about 5 percent of its area. You could build new cities housing 10 million people on raw open land, in four person households in single family dwellings on quarter-acre lots, with an equal amount of space allocated for roads, schools, parks, and commercial and industrial space, and it would only require 2,000 square miles. In the geography of vast California, that is an insignificant amount of land. Why not?

It is ironic that CEQA and related laws have made it almost impossible to build on “greenfields,” that is, on raw undeveloped land on the periphery of cities, and yet the laws are streamlined to fast-track infill development in relatively toxic and already densely populated urban environments. Perhaps in the interest of environmental justice, low income communities should be supporting laws to permit the expansion of California’s urban footprint.

The Tentacles of CEQA Intersect with Other Regulatory Beasts

It’s easy to digress into a discussion of urban planning, and ask why a green straightjacket has been thrown around every major urban center in California, but at the center of such a tangent one still finds omnipresent CEQA. And CEQA, for all of its regulatory tentacles, is only part of a consortium of similar regulatory creatures. The Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the California Global Warming Solutions Act (AB 32, passed by the state legislature in 2006), and seemingly infinite laws, executive orders, agency regulations, and court rulings pursuant to these and others, along with CEQA, have combined to make development in California nearly impossible.

For example, development proponents who testified in the Little Hoover Commission hearings repeatedly brought up a relatively recent regulation pursuant to AB 32, the requirement that any new housing development calculate the projected annual “vehicle miles traveled” (VMT) the residents will generate. Taking effect in 2018, this new analysis must be done in order to determine how much mitigating fees the developer will be assessed in order to fund mass transit or otherwise offset the anticipated greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles owned by residents of a new community.

But in the meantime, developers whose projects have been mired in the CEQA process since well before 2018 are now required to supplement the portions of their EIR that evaluated traffic impacts based on congestion with a new evaluation that estimates vehicle miles traveled. And while this VMT analysis is meant to supersede the traffic congestion as “the new lens for assessing transportation impacts,” potential congestion remains grounds for 3rd parties use CEQA to sue developers to stop their projects.

More generally, critics of CEQA have made clear that the law, in combination with other environmentalist inspired laws, have created a web of regulatory hurdles that are so unclear and so costly that only a small handful of housing developers, government agencies, or civil engineering contractors are big enough to navigate them. As one person testifying said, CEQA will turn a $1.0 billion project into a $1.5 billion project simply because when it takes ten years to go through the typical rounds of CEQA reviews, then debt financing taken out at 5 percent interest after 10 years will have ballooned up to a sum more than 50 percent higher than at the start.

Another compounding problem with CEQA and related laws designed to protect the environment is because so many years are required to get approval, by the time the design of a project is approved, the design has become obsolete.

Changing the rules in midstream, conflicting rules depending on the agency, an approval process that takes years if not decades, financing that dries up or is driven up to punitive levels, excessive, unreasonable fees, projects that take so long that if and when they finally get the green light, either the market or the technology has left them far behind. Start over. This is life with CEQA. This is California. For all its virtues, and there are plenty of them, environmentalism run amok is destroying economic opportunities for all Californians, and CEQA is the beating heart of the beast.

- Ringside: Is Photovoltaic Power Competitive? - December 13, 2024

- Ringside: Finding Water for the San Joaquin Valley - December 5, 2024

- Ringside: Californian Energy Use Compared to the USA and the World - November 29, 2024

They have become a “Super government”, strong willed, arrogant, and answerable to no one.

Basically, their message is “Don’t bother”.

No doubt abusing CEQA is one of the methods used by Marin County to prohibit low income and high density housing from being built? The wealthy Democrats who make up a majority of the population of Marin County don’t want housing equity for the homeless and those with low incomes mucking up their pristine environment?

Thank you, Mr. Ring. This is the kind of thing that should be regularly on nightly news across the state. I suspect that the agenda behind the Green religion prevents the severe problems caused by CEQUA from being exposed to the wider public.

While CEQA may need overhauling, the housing problem in California would seem to stem more from too many humans than from too much natural environment. I watch the farmland disappearing at an alarming pace each week for several years now, replaced with that one-time crop known as “houses” and humans, and the retail services and conveniences that goes with human lifestyles. Property tax revenues, government bonds, and special interest monies between taxpayer funds, unions, and political campaigns grease the wheels of “progress.” CEQA may be the only thing preventing cement from covering the entire state .

People complain about agricultural water use, but it is things like CEQA that stop individuals from building reservoirs on their property in favor of drilling a well as the permitting is easy. Much better that a 10, 20, or larger acreage vineyard catch winter runoff for their water needs than drill a well. CEQA is causing a lot of environmental damage when the big picture is considered. There are federal laws that cover environmental reporting. Just get rid of CEQA.

CEQA is a necessary and useful legal framework for bringing into the democratic decision-making environment the most inclusive and directly relevant public information and public common sense of informed common interests, outcomes, and sense of inter-generational responsibility.

The CEQA process is a demanding participatory one. It depends on frank acknowledgement of the commonality of or shared nature of the current and future living resources needs of most people now and of people (our children, the children of others) of the next and future generations. It is useful, prudent and necessary precisely because it is an interaction that works toward including information from as many people as possible and works by developing a more broadly informed and factually correct and useful body of understanding and a sense of the mutuality of responsibilities and interests.

Unlike many of the original projects which CEQA is there to enable the public to appraise, most (of course, not all) of the outcomes of CEQA actions put into the public hands make very clear the capacity of informed public scoping and evaluation for supporting, modifying, or disapproving of, the need and the functional usefulness. CEQA gives to all members of the public the legal standing that clearly reflects an understanding of public interest and of equal opportunity and equal protection under the law; by being thus enabled, all members of the public can factually work to reduce many sorts of potential harms while also making plain and making possible the kinds of potential benefits that any project can be seen to produce, both immediately and over time.

The problem with any statutory process or regulation that is aimed at bringing more and better information into the public political space to guide and limit and coordinate public and private interest fulfillment is NOT usually is not the capacity of the statute to produce common public interests and benefits and to promote or protect private, constitutionally recognized private needs and interests; the problem is the willingness of every citizen to act with integrity and with an unselfish view of the public interest, to see the present and inter-generational common interest as paramount.

The view of constitutional democracy and of public interest and public process expressed here is neither liberal nor conservative. It is democratic: it is supportive of rule of law governance in both form and function, and it has, does and will continue to serve common interests over and above self-interest and above poorly informed desired or expedient projects that ignore the public interest and scorn inter-generational responsibilities.

In the past two decades CEQA was been perverted by unions to extort “Project Labor Agreements” out of homebuilders and renewable energy developers. Don’t sign a PLA in advance of CEQA? Unions have lawyers on retainer ready to file lawsuits against CEQA approvals that will tie up those approvals in litigation for years. It doesn’t matter if your project is CEQA compliant, the attorneys will pick one of the 17 CEQA sections and delay you for years.

CEQA needs to be reformed and updated so it protects the environment but doesn’t become a tool to extort money and drive the cost of housing up.

Spoken like a true over educated scholar, or lawyer who works this system..

Your comments purport good oversight of projects yet decry the old adage “time is money”.

Most original infrastructure, like the LA Water district’s usurpation of Owens Lake and much of the “landscaping” and water districts that were created pre-CEQA are badly out of compliance, yet is CEQA trying to mitigate them? Oh, probably exempt..

by letting factories and cities be created else where in the state, lots of this could be reduced. Oh, sorry, no electricity or infrastructure, which should facilitate growth away from the urban landscape.

After a career living all around a city, and suburbs, people want to live away from it, but suffer longer commutes because even a convenience store is not allowed in their neighborhood.

Folsom/El Dorado Hills is a good example, that declared a moratorium on building (no water), then built the hundreds of houses along the freeway, and with no entrance ramps along US-50, they wind thru housing and shopping to get to it.

Down south the miles on wind turbines along I-10 are more and more of an eyesore since older turbines replaced by newer ones are never removed.. where is the mitigation?

And if CEQA is partly or wholly responsible for forest management l question their sanity on that as well.

CEQA “solutions” seem to just complicate the process due to special interests modifying sections that are critical to them ensuring they don’t lose control. Really need to take a scorched earth approach (heh), CEQA initially was written to cover only government actions, but the courts in the Friends of Mammoth decision made it applicable to private development. So consider modifying the law back to the pre-Friends of Mammoth decision, and then only governments need to deal with it.