Natural gas production. (Photo: ucr.edu)

How Do You Solve a Problem Like CEQA? Part Three

Solutions to CEQA

By Edward Ring, June 21, 2023 3:00 am

This is the third and final installment in a series of reports on the impact of the California Environmental Quality Act on development in California and ways to potentially improve the law. It is written in response to hearings conducted over the past three months by the California’s Little Hoover Commission.

What was never mentioned in the Little Hoover Commission’s hearings on CEQA, but deserves consideration, is to simply repeal the entire law. Get rid of it. The idea that development projects would suddenly proliferate, out of control, if CEQA went away is ridiculous. Every other law to protect the environment would still be in place, including the Endangered Species Act, the Global Warming Solutions Act (which should also be repealed), and the National Environmental Policy Act, which is the federal counterpart to CEQA and which is more than adequate to protect the environment.

Eliminating CEQA would go a long way towards restoring opportunities for low and middle income Californians, but eliminating CEQA is a fantasy. Equally impossible would be to eliminate the ability of private parties to sue developers under CEQA. This would eliminate the bounty hunters and lawyer trolls who have created a lucrative industry using CEQA to shake down developers. While it would also remove an avenue for members of low income communities to protect their neighborhoods, that benefit is overstated when developers target low income communities for high density housing, protected by laws that have exempted them from CEQA, and also permit them to circumvent local zoning restrictions. There is another path to environmental justice, which is to lower the cost-of-living, and the biggest barrier to lowering the cost-of-living is CEQA.

A solution to CEQA that might be politically viable would be to restrict 3rd party lawsuits to parties that are specifically concerned about environmental impact and reside in the affected communities. This reform, if it was properly calibrated, might reduce or eliminate greenmail, lawsuits brought by competitors to a developer, and settlement bounty hunters. Another solution, mentioned earlier, might be to eliminate all exemptions, and recognize that if CEQA is a necessary process to protect the environment, there is no justification to place any category of development outside its purview.

Here then, are some incremental, and not so incremental, solutions proposed for CEQA:

1 – Eliminate all exemptions. Anyone wanting an exemption is speaking just for their special interest.

2 – End anonymous lawsuits; require environmental standing to sue. Accept only environmental criteria for litigation. Only allow standing to people directly impacted on environmental grounds. For example, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) does not give standing to labor.

3 – Clarify the conditions under which if a development conforms to a county’s standing environmental impact report for that category of project, then it is not subject to further CEQA review.

4 – Allow applicants to rely on previously approved EIR. If a proposed project is consistent with the county’s specific general plan, community plan. and zoning, eliminate the requirement for additional environmental review.

5 – Make reviews of housing projects ministerial, or, make review of any project – including energy development – ministerial.

6 – Require the loser in CEQA lawsuits to pay the prevailing party’s legal fees.

7 – End duplicative lawsuits; once a plan or project is approved with CEQA it can be challenged in a lawsuit once but not multiple times for each subsequent agency approval.

8 – Do the CEQA process just once, with all involved agencies operating together, not sequentially.

9 – Change the timeline for notifying agencies of the objections to EIRs. Designate a final review step in the CEQA process after which further litigation is prohibited. This is already a provision of NEPA. As it is, objections including litigation are filed at the last possible moment, often in the final public hearing before approval of a project.

10 – For all private proposals, eliminate the requirement that the EIR include an evaluation of alternative sites for the project.

11 – Impose a maximum time limit on how long an agency has to respond to an initial or revised environmental impact report.

12 – Expedite the process so problems identified in an EIR review can be fixed right away by the developer. As it is every time the process is restarted there is potential for new claims.

13 – Match the CEQA remedy to the CEQA deficiency. Specify that while a court can order more CEQA analysis and mitigation, it cannot block a project or rescind a project approval unless there is a significant adverse health or safety impact if the project is constructed.

14 – Flaws found in EIRs are often extremely technical and it is often questionable whether or not a particular technical deficiency would prevent the project from being approved in its current form. Therefore if there is a technical flaw but it is not prejudicial and will not really make a difference, a harmless error standard should apply, such that if the project would be approved anyway notwithstanding the technical deficiency that should not be a basis for denying the EIR.

15 – Judicially enforce California Public Resources Code PRC § 21083.1. Judges should not require anything more than what is expressly required in CEQA statutes and guidelines. Doing this would make CEQA more predictable, which would improve the law and its effect on development.

16 – Replace the right to appeal with the right only to a writ of mandamus. This way if the court of appeal believes the appeal is frivolous they can deny the writ and hence avoid a full briefing, oral arguments, and having to write an opinion. A writ of mandamus can be evaluated within months. If an appellate court does think an appeal has merit, they can approve a writ of mandamus and then it becomes treated like an appeal. The reform language can include a provision that if there is a “likelihood” the petitioner is right, the appellate course must accept the writ.

17 – If a project is approved, that approval shall remain recognized for a set number of years even if rules are subsequently updated.

18 – Repeal CEQA entirely. Rely on NEPA and other environmentalist legislation to protect the environment from developments that may have a significant impact.

The Benefits of CEQA Reform

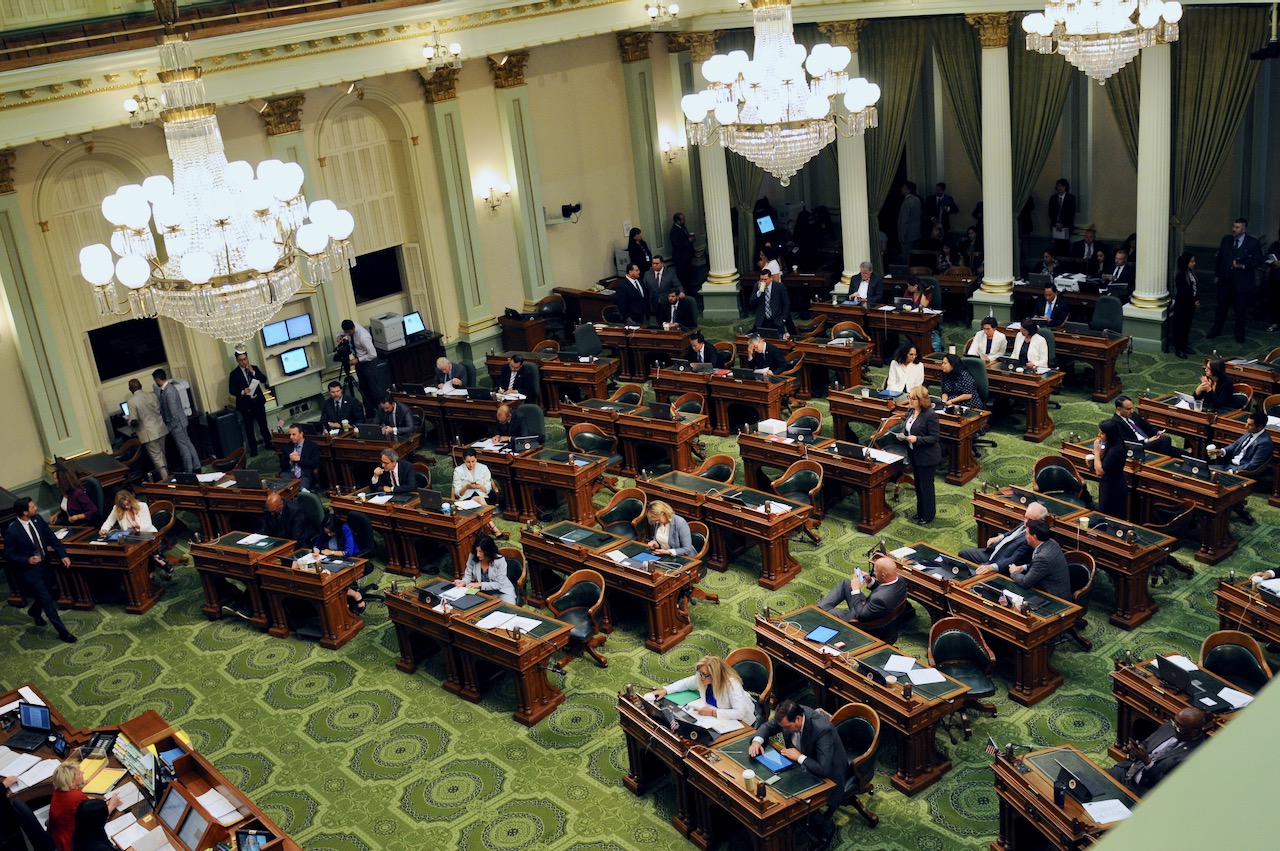

Despite objections from environmentalist organizations, environmental justice advocates, and some labor union representatives, there is a growing consensus within the State Legislature that something has to be done about CEQA. This is evident in the countless exceptions that the legislature has enacted to accelerate development of low income housing and renewable energy projects.

One of the most intriguing testimonies before the Little Hoover Commission came from Danny Curtain, representing the California Conference of Carpenters. He argued that a labor union is justified in seeking prevailing wages and a project labor agreement whenever a private developer receives public subsidies and streamlined permitting benefits. As he put it, “if you give the developer a break don’t let the developer take out profits on the backs of the workers.”

Curtain’s point is that if there is a special public benefit then you can argue the public sector now has equity in the project and therefore you can argue it is to some extent a public work and therefore should be subject to the labor laws impacting public works. This is a reasonable argument. One may object to the idea that public works should be subject to project labor agreements at all. But that is a separate debate.

The role of unions in CEQA raises a more fundamental question. How do you bring construction workers, or, for that matter, all skilled workers, back into middle class status? Do you accomplish this via union mandates or via business competition for workers in a prospering economy? As it is, there is a shortage of highly skilled workers, ready to take on more public works projects or work in California’s industrial sector. Where are the apprenticeship programs to address this shortage?

One of the last people to speak was involved with the Sierra Club, who proudly declared they “go to sleep with EIRs.” This person, and countless similarly committed activists and professionals, have become expert at using CEQA to stop projects. Whether it is housing, or critical enabling infrastructure, seemingly no major project, anywhere, is acceptable to them. CEQA is their weapon to stop California from building the physical assets to match its population. And for years, with increasing effect, it’s been working.

This is where unions, if they’re serious about seeing more workers acquire middle class status, may want to consider the upside of diminished CEQA statutes. If California’s civil engineering contractors were permitted to build practical solutions to supply the state with abundant energy and water, not only would this create tens of thousands of high paid construction jobs for highly skilled workers, it would lower the cost-of-living for every household in the state.

There are two paths to financial security for households. The traditional union solution is the path of higher wages. But an equally effective path with broader benefit is to lower the cost of life’s essentials – housing, water, energy, transportation and food. Union leadership in California should consider the impact of CEQA in this context, and if they do, realize their alliance of convenience with environmentalist extremists is not in the interests of all workers, even if it has worked to the more narrow benefit of their own memberships.

Reducing the power of CEQA may be the first of many steps necessary to rescue California from a mentality of scarcity and rationing that, to-date, has only been challenged rhetorically. Declaring more exemptions to CEQA is a terrible solution. The many steps recommended here may fall well short of a complete repeal of the law, but would all nonetheless help make California a place where working families may have a better chance to find a good job, afford to pay their bills, and begin to achieve financial security for their households.

CEQA reform, however, is only one big part of a much bigger debate. Do Californians want to develop their state again with the confidence and efficiency that defined the big projects of the 1950s and 1960s, when roads, reservoirs, and a power grid were constructed using mostly public money and for a time actually delivered an oversupply of affordable transportation, water and energy? Do Californians want to recognize that setting an example that other nations of the world find attractive and practical? Because to do that, more than CEQA will have to be revised.

For example, modern natural gas power plants employ combined cycle designs that harvest waste heat from the natural gas-fired turbine to produce steam to drive a second turbine. But new combined cycle designs replace the steam with helium, which harvests waste heat at much higher temperatures than steam can, which means less heat wasted to the atmosphere, greatly increasing efficiency. This advanced design can convert up to 80 percent of the embodied energy in natural gas fuel into electricity. Why not reclassify these new ultra-efficient natural gas solutions as renewable energy?

For that matter, why aren’t Californians at the forefront of both small modular and large next-generation nuclear reactor development, and reclassifying them as renewable energy?

Why can’t advanced, still emerging hybrid automotive technologies, which use a battery one-tenth as heavy to harvest the energy otherwise wasted from braking and downhill momentum, remain eligible for sale in California after 2035?

Why isn’t the California Water Commission required to declare “beneficial use” of water diversions to be equally applicable to urban and agricultural users as it is when allocated to preserving aquatic ecosystems?

Answering questions like these with policies that are once again designed to nurture economic growth instead of economic stagnation is a prerequisite for California to recover prosperity for every worker in the state. Unions should recognize this, as should social justice activists and progressives. The impact of CEQA in particular, and overwritten environmentalist legislation in general, only benefits special interests. It is time to restore balance between what is possible to protect the environment, and what is necessary to empower the people living here. Reforming CEQA is the first step in that process.

- Ringside: Why Data Centers Will Create Electricity Abundance - March 12, 2026

- Ringside – Building the Abundant Water Coalition - March 5, 2026

- Ringside: Can Energy and Water Interests Find a Common Agenda? - February 26, 2026