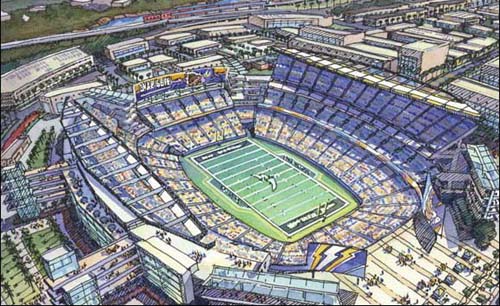

The proposed and eventually voted down new San Diego Chargers Stadium. (Wikipedia)

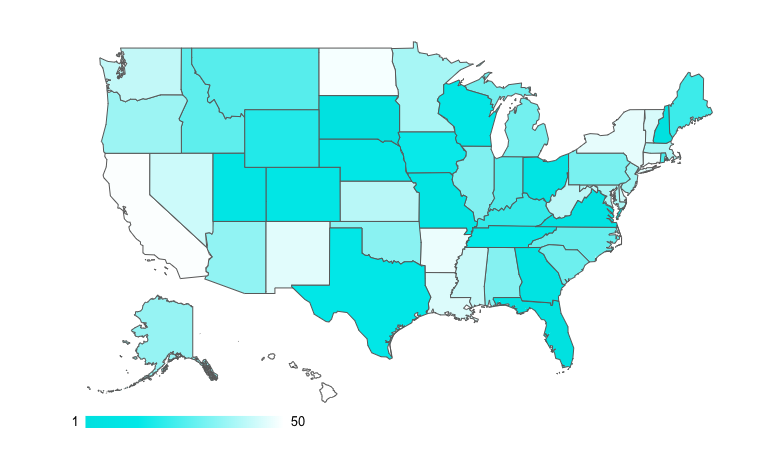

California Leads The Way In Building New Stadiums And Arenas By Not Using Taxpayer Money

A new stadium in Sacramento has shown the recent legacy of California voters and lawmakers voting no on spending billions of taxpayer money

By Evan Symon, November 22, 2019 11:57 am

Late last month Sacramento was granted a new professional soccer team by the MLS. Carrying on the name of the current lower division club, the Sacramento Republic, the team is set to play in the MLS in 2022. And they’ll begin in the brand new $226 million tentatively-titled Railyards Stadium.

The new privately funded soccer stadiums in California

Normally a stadium costing hundreds of millions of dollars would come with public outcry over the price tag. In past years citizen and fan groups have brought city councils to their knees over public money going to giant stadiums most of them barely used with the explanation that it would boost profits of surrounding businesses like restaurants and bars. But in Sacramento there was no debate to be had, as the stadium was entirely privately funded. Although, as KOVR Channel 13 reported, The Sacramento City Council unanimously agreed to loan up to $27.2 million to pay for the infrastructure for the planned Sacramento Republic FC Railyards stadium and developments.

The last MLS team to have a privately funded stadium was also in California, with LAFC’s new $350 million dollar stadium, Bank of California Stadium, being entirely paid for by a mix of owners, investors, and sponsors.

Outside of California, recent MLS stadiums such as Allianz Field in St. Paul, Minnesota have been entirely or largely privately paid for, but have included hidden caveats such as tax-exemptions from the state to operate. But most post-LAFC stadiums seem to be following California’s trend.

“There used to be this thinking that stadiums benefited everyone,” said Michael Walker Jr., an urban planner who has worked on stadium planning before. “But now we know, thanks to the Stanford study, that they don’t help local economies at all. At most, to the average non-sport fan, a good team may temporarily boost the stature of a city and possibly increase tourism.

The people in California weren’t the first to react to this, because teams like the Seattle Supersonics in 2008 and the Cleveland Browns in 1995 left after taxpayers refused to finance new stadiums. In some cases, they voted against paying higher taxes for them. That’s how you wound up with some owners, like the Colts old owner, literally packing up and moving the team overnight from Baltimore to Indianapolis. But California really led the wave for stadiums to be built privately and not with taxpayer money.”

San Diego loses and wins over a new stadium vote

San Diego fans know this too well. In the mid 2010’s, the San Diego Chargers, led by owner Dean Spanos, were looking to get a new stadium to replace the aging SDCCU Stadium and threatening to leave San Diego if they didn’t get a publicly funded stadium. The Chargers began making inquiries to Los Angeles and other markets looking for an NFL team, but fans and voters alike were more appalled at how he was, in their eyes, holding the city hostage to pay for a new stadium.

Finally, in 2016, Measure C appeared on the ballot in San Diego County. The owners thought citizens would vote for it, but surprised them when the measure failed 57% to 43%. With no other option short of paying for a new stadium with their own money and investors money, they simply moved the team to Los Angeles, where they are set to share a new stadium with the Los Angeles Rams next year.

The move has been widely seen as a disaster, with the Chargers not selling out a temporary 20,000 seat stadium they’re playing at outside of Los Angeles, with games routinely having a majority of opposing teams fans coming into the stadium during games. Meanwhile, voters in San Diego have been nationally praised for not giving into pressure and not giving away over half a billion dollars for a stadium that would have been used less than a dozen times a year.

The decision also influenced the people of Oakland to not acquiesce to the Raiders also long-standing demands of a new stadium, and are set to move to Las Vegas next year.

A $5 billion dollar stadium in Los Angeles built without a dime of taxpayer money

The new stadium, SoFi Stadium, and surrounding developments that the Chargers and Rams will be moving into next year will cost just under $5 billion dollars, and set the new record for the most expensive privately funded stadium in the world.

“LA and San Diego both dodged that bullet,” noted Diane Jackson, an architect with experience in presenting large projects to cities across California. “It’s a massive stadium. I mean, $5 billion. Can you imagine Inglewood having to front some of that? Or San Diego? Or even Los Angeles? They’d hate the teams even more on that principle alone.

And I’ve seen this before with hospitals and shopping complexes. Now that this $5 billion number is out there, even with the whole complex being built around it, it can be brought up during hearings and before votes. You know ‘You’re asking for our money on this $400 million building, when this $5 billion billion was given funding by private financiers?’

California has made building new stadiums based on total or partial taxpayer money very hard to do. There’s a price point out there now, and I guarantee you everyone looking to build a new stadium has seen that number and are thinking of ways around it right now.”

“They’re going to say that LA is a bigger market or things like that, but all the other side has to point to is how many fans actually turn up at games to justify the cost. It’s a new era. Really.”

The Sacramento Kings exception

In addition to influencing the Raiders departure because of the public’s refusal for paying for a new stadium, the NBA’s Golden State Warriors also followed the trend. Opening this year in San Francisco, the $500 million Chase Center was entirely privately financed. At the same time the Chase Center’s finances were discussed, a similar arena in Milwaukee had their funding approved, but only because the team was given an ultimatum. The matter ended up going before the Wisconsin Senate, where they approved $250 million of Wisconsin taxpayer money to go to one arena.

In California there has only been one exception during the privately-financed stadium wave. The $534 million Golden 1 Center, the new home of the NBA’s Sacramento Kings, was built during the mid-to-late 2010’s. However, unlike having to be bailed out by the state, have voters directly pay for a new development, or, like in the case of Marlins Park in Miami in the early 2010’s, have the owner completely lie about not being able to afford a new stadium on their own and get an entire SEC investigation to be called on about it, the Kings went a more casual way with it.

Needing to revitalize K Street in Sacramento and to remove part of a long suffering mall, the City of Sacramento approved over $200 million in bonds to be sold.

“They got public money, but they got it in a way that did the least amount of harm to taxpayers. Plus, as a city planner, I can say that is a revitalization project that they researched extensively to work. It’s not like the Baltimore Waterfront’s failure in Baltimore in the 90’s. They chose the area well and to the point that walking around the city, especially to and from games and concerts, benefits everyone. It’s one of the rare successful examples of it.

They’re an exception on many levels.”

The legacy of California’s avoidance of taxpayer stadium waste

Meanwhile, back in the MLS, two new stadiums outside of California are also being built for new teams, one in St. Louis, and one in Austin. The St. Louis group wanted $80 million in taxpayer money to help finance a new stadium, but it led to massive public outcry. In 2017, the question of the stadium being funded by the public came to a vote, where those opposing the measure got some help.

“We were looking for stadiums that had been paid for completely by team itself, or something like that,” explained Adam Davis, a St. Louis soccer fan who helped oppose the vote. “And we kept seeing stadium after stadium in California. And we brought all of them up at meetings and even on ads on TV.

And it worked.”

The measure had been narrowly defeated 53% to 47%.

“If California teams, especially LAFC, had not built their stadiums on non-public money, the people of St. Louis would have been saddled with $250 million. A lot of people here don’t like California, but we owe that to all of you,” said Davis, audibly laughing.

The stadium effort was regrouped in 2018, where the team managed to get a privately-funded stadium package put together to the applause of St. Louis lawmakers and citizens.

Austin’ team avoided that drama and simply privately financed their stadium from the get-go.

“California is influencing a lot of others,” noted Walker Jr. “Two decades ago, it would have been owners threatening to move teams to get new stadiums. Now, many fans are apathetic. Owners can afford new stadiums, or they can with investor help, and taxpayers don’t want this burden.”

“It’s famous in some circles, but Montreal took 30 years to pay off their Olympic Stadium. A lot of stadiums increase ticket prices in stadiums the people paid for. The owners get revenue in stadiums built by taxes.”

“But cities and owners are seeing this movement against wasting money on stadiums now. It’s saving cities a ton, and owners get more control in customizing the stadium. Plus fans get their team, their games.”

“This has been an issue for decades, fights over publicly funded stadiums most fans are priced out of or don’t go to. This doesn’t solve everything, but it’s working out for everyone.”

“And you have stubborn Californians who didn’t want another tax hike or more city debt to thank.”