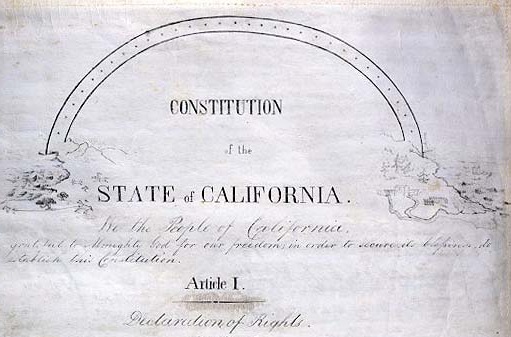

California Constitution. (Photo: www.sos.ca.gov)

Direct Democracy and California’s Constitution Article II

Part l: Initiatives

By Chris Micheli, April 8, 2019 5:15 am

The purpose of this article is to examine California’s three forms of direct democracy, which are set forth in Article 2 of the state constitution. California’s forms of direct democracy play a critical role in state governance and the legislative process. There are important provisions found in Article II, as well as a number of appellate court decisions that interpret these provisions.

Article II deals with four topics: voting, initiative, referendum, and recall. This article of the California Constitution contains twenty provisions. While there are constitutional provisions related to voting in this state, this article does not address that topic, which is unrelated to the provisions dealing with direct democracy. California is one of 24 states to have an initiative process, the most critical aspect of direct democracy.

Fundamental to the California Constitution is that “All political power is inherent in the people.” Government is instituted for the people’s protection, security, and benefit, and they have the right to alter or reform it when the public good may require it.

INITIATIVES

Defined

The initiative is the power of the electors to propose statutes and amendments to the Constitution and to adopt or reject them. An initiative measure may be proposed by presenting to the Secretary of State a petition that sets forth the text of the proposed statute or amendment to the Constitution and is certified to have been signed by electors equal in number to 5 percent in the case of a statute, and 8 percent in the case of an amendment to the Constitution, of the votes for all candidates for Governor at the last gubernatorial election.

CHRIS MICHELI DISSECTS CALIFORNIA LIKE NO ONE ELSE—ONLY ON THE GLOBE:

• The Legislature and California Constitution Article IV (part II)

• The Legislature and California Constitution Article IV (part I)

• The Governor and California’s Constitution Article V

• Everything You Thought You Knew About Lobbying is Probably Wrong

• Unique Aspects of California’s Electoral System

• Who Makes the Rules for the Judiciary?

The Secretary of State must then submit the measure at the next general election held at least 131 days after it qualifies or at any special statewide election held prior to that general election. The Governor may call a special statewide election for the measure. An initiative measure embracing more than one subject may not be submitted to the electors or have any effect.

Prohibitions

An initiative measure may not include or exclude any political subdivision of the State from the application or effect of its provisions based upon approval or disapproval of the initiative measure, or based upon the casting of a specified percentage of votes in favor of the measure, by the electors of that political subdivision. An initiative measure may not contain alternative or cumulative provisions wherein one or more of those provisions would become law depending upon the casting of a specified percentage of votes for or against the measure.

Process

Proposing statutes and constitutional amendments is done by presenting a petition to the Secretary of State. That written petition must include the text of the proposed statute or constitutional amendment. Before circulation of an initiative petition for signatures, a copy must be submitted to the Attorney General who then prepares a title and summary of the measure as provided by law.

If the Attorney General determines a fiscal analysis is necessary, the measure is sent to the Department of Finance and Joint Legislative Budget Committee for that fiscal analysis. When the Title and Summary has been completed (usually 15-45 days from date of submission), this becomes the “Official Summary Date”

The Secretary of State certifies the petition based upon the signatures collected. Proponents have 180 days for signatures to be obtained. Only registered voters can sign in their county of registration. The measure is then placed on the ballot of the next statewide general election at least 131 days after the measure qualifies.

An initiative statute approved by a majority of voters takes effect on the fifth day after the Secretary of State files the statement of the vote for the election at which the measure is voted on. Nonetheless, the measure may provide that it becomes operative after its effective date. If the provisions of two or more measures approved at the same election conflict, the provisions of the measure receiving the highest number of affirmative votes prevails.

An initiative cannot name any individual to hold any office, or name or identify any private corporation to perform any function or to have any power or duty, may be submitted to the electors or have any effect.

Key Cases Interpreting Constitutional Provisions Related to Initiatives

Power Is Absolute

The power vested in the voters to decide whether the Legislature can amend or repeal initiatives is absolute and includes the power to enable legislative amendment subject to conditions attached by the voters.

Power of the People

When the people established the Legislature, they conveyed to it the full breadth of their sovereign legislative powers, but when they adopted the initiative power, they restored to themselves only a shared piece of that power. The people’s initiative and referendum power and the constitutional provisions mandating electoral review of particular actions by the Legislature do not prohibit the Legislature from using advisory ballot measures to determine the electorate’s position on whether the Legislature should exercise its power to petition for and participate in a federal constitutional change.

Placement on the Ballot

Placing two propositions for state constitutional amendments on the same ballot as a California gubernatorial recall election, rather than placing them on the ballot at the next regular election, would violate the provision of the California Constitution requiring that a vote be held on initiatives at the next general election at least 131 days after qualification.

Power Resides with the People

The constitutional provision for initiatives rests on the theory that all power of government ultimately resides in the people.

Initiative Versus Referendum

The initiative power is not a corollary to the referendum power in all circumstances, and thus a court is not required to imply the right to initiative where the right to referendum is expressly stated. The initiative allows voters to propose new legislation; in contrast, the referendum permits voters to reject legislation that has already been adopted.

Invalidating an Initiative

An initiative measure must be upheld unless its unconstitutionality clearly, positively and unmistakably appears. When an initiative provision is invalid, the void provision must be stricken, but the remaining provisions should be given effect if the invalid provision is severable.

Pre-Election Challenges

Pre-election challenges to an initiative measure need not be brought while petitions still are being circulated and prior to the time that a measure qualifies for the ballot; adopting such a rule would place an unreasonable and unrealistic burden on those who may wish to challenge an initiative measure, as well as on the courts. It is appropriate to resolve a single subject challenge to an initiative measure prior to the election when a court determines that the challengers have demonstrated a strong likelihood that the initiative violates the state constitution’s single subject rule. Under such circumstances, deferring a decision until after the election not only will defeat the constitutionally contemplated procedure reflect in the language, but may contribute to an increasing cynicism on the part of the electorate with respect of the efficacy of the initiative process. Severability is not available when an initiative measure violates the single subject rule.

Challenging an Initiative’s Validity

Neither the Governor, the Attorney General, nor any other executive or legislative official has the authority to veto or invalidate an initiative measure that has been approved by the voters. It would not violate the separation of powers doctrine of the state constitution to permit the official proponents of an initiative to assert the state’s interest in the validity of the initiative in a judicial proceeding in which the validity of the measure is challenged. In an action challenging the validity of an initiative measure, because the official initiative proponents are permitted to intervene in order to supplement the efforts of public officials who may not defend the measure with vigor, it is appropriate to view the proponents as acting in an analogous and complementary capacity to those public officials, namely as asserting the people’s interest in the validity of a duly enacted law. California courts have an obligation to liberally construe the provisions of the state constitution relating to the initiative power to assure that the initiative process is not directly or indirectly annulled. Once an initiative measure has been approved by the requisite vote of electors in an election, the measure becomes a duly enacted constitutional amendment or statute. Once an initiative measure has been approved by the requisite vote of electors in an election, the measure becomes a duly enacted constitutional amendment or statute.

Evaluating Constitutionality

When evaluating the constitutionality of initiative measures, the court of appeal does not consider or weigh the economic or social wisdom or general propriety of the initiative, but evaluates constitutionality in the context of established constitutional standards. The initiative power must be liberally construed to promote the democratic process. An initiative measure does not violate the single subject requirement if, despite its carried collateral effects, all of its parts are reasonably germane to each other and to the general purpose or object of the initiative. The single subject rule is designed to avoid confusion of either voters or petition signers and to prevent subversion of the electorate’s will.

Determining the Electorate’s Intent

Initiatives are subject to the same constitutional analysis as statutes. To determine the electorate’s intent in passing an initiative, it is best to look at the language of the initiative itself.

Extent of Single Subject Rule

An initiative does not violate the single subject rule merely because it amends two statutory schemes. The single subject provision does not require that each of the provisions of an initiative measure effectively interlock in a functional relationship; it is enough that the various provisions are reasonably related to a common theme or purpose. An initiative measure does not violate the single subject requirement if, despite its varied collateral effects, all of its parts are reasonably germane to each other and to the general purpose of object of the initiative.

Satisfying the Single Subject Rule

For purposes of satisfying the single subject requirement under the state constitution, the common purpose to which various provisions of an initiative measure relate cannot be so broad that a virtually unlimited array of provisions could be considered germane thereto and joined in the proposition, essentially obliterating the constitutional requirement. An initiative may have collateral effects without violating the single subject rule.

Extent of the People’s Powers

The people’s reserved powers of initiative and referendum are limited to adoption or rejection of statutes. The people’s powers do not encompass all possible actions of a legislative body. An initiative which seeks to do something other than enact a statute, such as rendering administrative decision, adjudicating a dispute, or declaring by resolution the views of the resolving body is not within the initiative power reserved by the people. There is no constitutionally protected right to place an invalid initiative on the ballot. Judicial review of an initiative before the petition has been circulated for signatures does not violate the constitutional initiative power.

Role of the Attorney General

Despite the courts’ duty to jealously guard the people’s right of initiative and referendum, noncompliance with the Elections Code can result in disqualification from the ballot. The title and summary of an initiative or referendum prepared by the Attorney General are presumed accurate, and substantial compliance with the “chief purpose and points” statutory provision is sufficient. By statute, the Attorney General is required to summarize the chief purpose and points of an initiative or referendum measure, and if reasonable minds can differ as to whether a particular provision is or is not a chief point of the measure, the determination of the Attorney General should be accepted.

Presumption of Validity

Statutes enacted by the electorate through the powers of initiatives and referendum, like the Legislature’s enactments, are presumed to be valid. The voters’ power to decide whether or not the Legislature can amend or repeal initiative statutes is absolute and includes the power to enable legislative amendment subject to conditions attached by the voters. The electorate’s legislative power is generally coextensive with the power of the Legislature to enact statutes. The Legislature is not the exclusive source of legislative power; the constitution also includes the people’s power of initiative and referendum. The court’s role in reviewing an initiative measure is imply to ascertain and give effect to the electorate’s intent guided by the same well-settled principles it employs to give effect to the Legislature’s intent when it reviews enactments by that body. The courts do not pass upon the wisdom, expediency or policy of enactments by the voters any more than it would enactments by the Legislature.

Reserved Power

The initiative and referendum are not rights granted to the people, but powers reserved by them in the California Constitution. The people’s reserved power of initiative in the California Constitution is greater than the power of the legislative body; the latter may not bind future Legislatures, but by constitutional and charter mandate, unless an initiative measure expressly provides otherwise, an initiative measure may be amended or repealed only by the electorate and thus through exercise of the initiative power the people may bind future legislative bodies other than the people themselves. If doubts can reasonably be resolved in favor of the use of the people’s reserve power of initiative and referendum in the state constitution, courts will preserve it. Statutes and constitutional provisions adopted by the voters must be construed liberally in favor of the people’s right to exercise the reserved powers of initiative and referendum. California Constitution only allows the Legislature to amend initiative statutes as allowed by the electorate.

Revision Versus Amendment

In order to constitute a qualitative revision in the state constitution which may not validly be enacted by voter initiative, a constitutional measure must make a far-reaching change in the fundamental governmental structure or the foundational power of its branches as set forth in the state constitution. Although the initiative process may be used to propose and adopt amendments to the California Constitution, that process may not be used to revise the state constitution. In determining whether a state constitutional provision is an amendment or a revision that may not be validly enacted by initiative, courts examine both the quantitative and qualitative effects of the measure on California’s constitutional scheme.

Effect of Approval

Under California law, once an initiative measure was approved by the voters, the measure became a duly enacted constitutional amendment or statute.

Interpreting an Initiative

The first task in statutory construction is to examine the language of the statute enacted as an initiative, giving the words their usual, ordinary meaning. In interpreting a voter initiative, the supreme court applies the same principles that govern the construction of a statute.

Construing Language

Statutory language enacted by a voter initiative must be construed in the context of the statute as a whole and the overall statutory scheme in light of the electorate’s intent. When statutory language enacted by voter initiative is ambiguous, courts refer to other indicia of the voters’ intent, particularly the analyses and arguments contained in the official ballot pamphlet.

Review by Courts

A statute governing the process by which a proposed ballot initiative measure was submitted for public comment, which specified that any amendments submitted for comment must be reasonably germane to the them, purpose or subject of the measure as originally proposed, did not preclude substantive amendments and was intended to create a comment period to facilitate feedback, rather than a broad public forum; the comment period was intended to allow the public to suggest amendments or correct flaws, a limitation imposed on amendments was a lenient one, and by ensuring that comments would be transmitted directly to the proponents, the Legislature signaled its intent that comments were for the benefit of proponents, not for the purpose of fostering public discussion. When reviewing ballot initiative measures, a court passes no judgment on the wisdom, efficacy or soundness of the proposal before it. Courts do not give consideration to possible interpretive or analytical problems that might arise should the measure become law. Review is limited to points necessary to resolve basic questions before the court.

No Violation of Single Subject Rule

An initiative measure does not violate the single subject requirement if, despite its varied collateral effects, all of its parts are reasonably germane to each other and to the general purpose or object of the initiative. The single subject rule does not require functional interrelationship or interdependence of provisions or showing that each one of the measure’s several provisions was capable of getting voter approval independently of other provisions.

- Death Deeds in California - February 27, 2026

- Sources of Law - February 26, 2026

- Commercial Fishing - February 26, 2026

Based on the content of this article, not one of the three branches of California’s government may step in and thwart the will of the people, but this is exactly what happened before the General Election of 2018 when Proposition 9 (Tim Draper’s Three State Initiative) was removed by the CA Supreme Court under the belief that “great harm” could come to the state. This is not a measure that is applicable in removing an initiative from the ballot. The will of the people is to be inviolate, yet the court overstepped it bounds. Nothing was done to the court for violating California’s constitution. And you wonder why those in the north state want to split the state up; there are no rules, only subjects to the masters under the dome.