The Legislature and California Constitution Article IV

A important Civics refresher course – Part ll

By Chris Micheli, April 5, 2019 2:30 am

The purpose of this article is to examine the constitutional provisions related to California’s Legislature and some of the appellate court decisions that provide insights into how these provisions are interpreted by the courts. Part I is here.

Part II – Selected Court Decisions

There have been numerous court decisions over the past one hundred years interpreting key provisions of Article IV. The following cases highlight some of the key decisions interpreting these constitutional provisions.

Changing the Words of Statutes

There is a presumption of change of legislative purpose arising from a material change in the wording of a statute.

The Legislature is presumed to have intended to change the effect of a statute by an amendment which deliberately and clearly changes the language substantially.

CHRIS MICHELI DISSECTS CALIFORNIA LIKE NO ONE ELSE—ONLY ON THE GLOBE:

• Direct Democracy and California’s Constitution Article II

• The Legislature and California Constitution Article IV (part II)

• The Legislature and California Constitution Article IV (part I)

• The Governor and California’s Constitution Article V

• Everything You Thought You Knew About Lobbying is Probably Wrong

• Unique Aspects of California’s Electoral System

• Who Makes the Rules for the Judiciary?

Authority to Repeal Laws

A corollary of the legislative power to make new laws is the power to abrogate existing ones. In other words, what the Legislature has enacted, it may repeal. At the core of the legislative power is the authority to make laws. The legislative power that the state constitution vests is plenary. Under the legislative power of the state constitution, the entire lawmaking authority of the state, except the people’s right of initiative and referendum, is vested in the Legislature, and that body may exercise any and all legislative powers which are not expressly or by necessary implication denied to it by the constitution. Only where the state constitution withdraws legislative power will the state supreme court conclude an enactment is invalid for want of authority.

Constitution Prohibits Certain Legislative Actions

Courts do not look to the constitution to determine whether the Legislature is authorized to do an act, but only to see if it is prohibited. Unlike the federal constitution, which is a grant of power to Congress, the California Constitution is a limitation or restriction on the powers of the Legislature. The judicial branch, not the legislative, is the final arbiter of the constitutionality of a statute.

Doubt Construed in Favor of Legislature

If there is any doubt as to the Legislature’s power to act in any given case, that doubt should be resolved in favor of the legislature’s action.

Legislative Findings

The determination of whether a program at issue serves a public purpose is generally vested in the Legislature. Though not binding on the courts, legislative findings are given great weight and will be upheld unless they are found to be unreasonable and arbitrary. Because legislative power is practically absolute, constitutional limitations on legislative power are strictly construed and may not be given effect as against the general power of the legislature unless such limitations clearly inhibit the act in question.

Limiting Rights or Duties

The Legislature is fully within its power to set forth a right or duty in statute and limit it at the same time in any way it chooses so long as it is not under constitutional compulsion to leave that right unrestricted.

Legislature Cannot Bind Future Legislatures

One legislative body cannot limit or restrict its own power or that of subsequent legislatures and, therefore, the act of one legislature does not bind its successors.

Legislature Can Adopt and Change Its Procedures

The Senate may adopt any procedure and change it at any time and without notice, and cannot tie its own hands by establishing unchangeable rules. The constitutional provision declaring that any member of the Legislature who is influenced in his official action by any reward or promise is guilty of a felony and precluding that individual from holding any public office or public trust did not have any effect whatever upon the power expressly given to the Legislature to expel its members.

Investigations of Legislators

The Senate has power to investigate charges of bribery against its own members and, in the exercise thereof, may summon and examine witnesses.

Delegation of Legislative Authority

An unconstitutional delegation of legislative authority occurs if a statute authorizes a person or group other than the Legislature to make a fundamental policy decision or fails to provide adequate direction for the implementation of a fundamental policy determined by the Legislature.

Legislative Delegation Internally

The Legislature cannot ratify a committee’s exercise of authority which the legislature could not lawfully delegate to the committee in the first instance. The Legislature cannot constitutionally delegate legislative authority to one house as to do so would violate bicameral and presentment clauses of the State Constitution.

Delegation to Counties

The State may, except where the people have not restricted such power, delegate to counties functions belonging to it and take back functions that have been delegated.

Roles of Legislative and Judicial Branches

Subject to constitutional constraints, the Legislature may enact legislation, but the judicial branch interprets that legislation.

Initiative Sponsors Defending Ballot Measure

It would not violate the separation of powers doctrine of the state constitution to permit the official proponents of an initiative to assert the state’s interest in the validity of the initiative in a judicial proceeding in which the validity of the measure is challenged. Asserting the state’s interest in the validity of a challenged law is not exclusively an executive function. The ability of official initiative proponents to defend a challenged initiative measure on behalf of the state does not improperly interfere with the discretion the Attorney General may possess to decline to defend a challenged measure or to decline to appeal from an adverse judgment when the Attorney General is of the view that a challenged initiative measure is unconstitutional under the separation of powers doctrine.

Presentation of Bills to the Governor

Because the Legislature is vested with the exclusive authority to determine whether the formalities for enactment of a statute have been fulfilled, it follows that a court cannot retry, as a question of fact, the Legislature’s determinations. The lawmaking power of the statute is vested in the legislature. While the constitution has prescribed the formalities to be observed in the passage of bills and the creation of statutes, the power to determine whether these formalities have been complied with is necessarily vested in the legislature itself since, if it were not, it would be powerless to enact a statute. When the Chief Clerk of the Assembly retrieves a bill from the Governor, he thereby curtails the presentation period required by the Constitution. If the Legislature determines retrieval was inappropriate, it can direct the Chief Clerk to promptly fulfill the presentation requirement by providing the Governor with the full period for review of the bill and courts should not second-guess that determination. A bill is not presented to the governor unless it is in the physical possession of the governor for a period of time, not more than 30 days, necessary to permit the governor to deliberate on the bill. The Governor’s act of returning the bill to the Legislature ends his own time for deliberation and the bill itself is put beyond the governor’s possession. The Legislature may retrieve a bill after it has been presented to the Governor. Where Assembly records reflected that, after retrieval of the bill from the governor, on motion of its author and with unanimous consent, the bill was withdrawn from engrossing and enrolling and was sent to the inactive file, it was later withdrawn from the inactive file and returned to enrollment and was the presented to the governor at that time.

Conflict of Laws with Constitution

Where statutes conflict with constitutional provisions, the latter must prevail.

Statutes Cannot Conflict with Constitution

The Legislature cannot act by enacting a statute that contravenes a constitutional provision.

Use of General Terms

General terms may be used in a statute to describe things according to the common understanding of such terms.

Meaning of Language

The Legislature is presumed to know the meaning of language. The presumption of change of legislative purpose arises from material change in the wording of a statute.

Presumption with Use of Words

The Legislature will be presumed to have used words in the precise and technical sense previously placed on such words by the Supreme Court.

Retroactive Laws

A retroactive law is one that relates back to a previous transaction and gives it some legal effect that is different from that which it had under law when it occurred.

Vague Statutes

A statute so vague and uncertain that a person of ordinary intelligence cannot understand it is invalid.

Criminal Statutes

A criminal statute which is so indefinite, value and uncertain that the definition of the crime or standard of conduct cannot be ascertained therefrom is unconstitutional and void.

Judicial Policymaking

If a court reads language into the statute, it must steer clear of judicial policymaking in the guise of statutory reformation and avoid encroaching on the legislative function in violation of the separation of powers doctrine. A court may reform or rewrite a statute to render it constitutional only when it can say with confidence that (1) it is possible to reform the statute in a manner that closely effectuates policy judgments clearly articulated by the enacting body and (2) the enacting body would have preferred the reformed construction to invalidation of the statute.

Reformation of Statutes

As a general matter, it is impermissible for a court to reform the statute to save it from invalidation under the constitution by supplying terms that disserve the legislature’s or electorate’s policy choices. By contrast, when legislative intent regarding a policy choice is clear, revision that effectuates that choice is not impermissible merely because it requires insertion of more words than it removes.

Term Limits Are Constitutional

A California constitutional amendment establishing term limits for state officeholders did not violate the First and Fourteenth Amendment rights of voters to vote for a candidate of their choice or asserted right of an incumbent to again run for his or her office. Term limits did not constitute discriminatory restriction and were of minimal impact on plaintiff’s rights was justified by the state’s legitimate interest in avoiding unfair incumbent advantages. Ballot measure gave voters sufficient notice that the proposition-imposed lifetime, rather than consecutive, term limits. Official proponents of a ballot measure were entitled to intervention as a right of action and the Secretary of State did not adequately represent proponents’ interests.

Restrictions on Running for Office

A provision of the constitution that makes an individual ineligible to be a member of the Legislature unless he is an elector and has been a resident of his district for one year immediately preceding the election contemplates that districts will be established at least one year before the election and where, under reapportionment plan, they are not so established, then the constitutional provision cannot apply. Inequalities among groups of electors are the inevitable byproduct of reapportioning a legislative body whose members are elected for staggered terms, and the supreme court was not free to obviate them where they did not constitute an invidious discrimination violative of the equal protection clause of the Fourteen Amendment.

Legislature Judges Qualifications

The provisions of the constitution confer exclusive jurisdiction on the legislature to judge the qualifications and elections of its members. The constitutional power conferred on the Assembly over elections and qualifications of its members extends to and includes primary elections.

Challenge to Lawmaker’s Support for Foreign Government

In view of the state constitution’s provision that each house shall judge the qualifications and elections of its members, the courts were without jurisdiction of the action seeking disqualification of an assemblyman because of his alleged support of North Vietnam against the United States during the Vietnam War or to enjoin the Attorney General, Secretary of State and County Registrar from certifying election results, swearing in, or disbursing money to the assemblyman if he were reelected and ordering return to public treasury of legislative salary previously paid, notwithstanding the constitutional provision that notwithstanding any other provision of law that no person who advocates support of a foreign government against the United States in event of hostilities shall hold any office or employment under the State.

Legislature Adopts Internal Procedures

Each house of the Legislature has the power to adopt any procedure and to change it at any time and without notice. California Assembly and Senate have the power to adopt their own rules of proceeding including rules for hearings and notice, and these rules of proceeding are the exclusive prerogative of each house.

Proceedings Refer to Entire Legislature

The term “proceeding” that authorizes the Legislature’s self-government of its internal affairs does not refer to activities engaged in by individual legislators, but rather to activities by which the Legislature as a whole conducts its business.

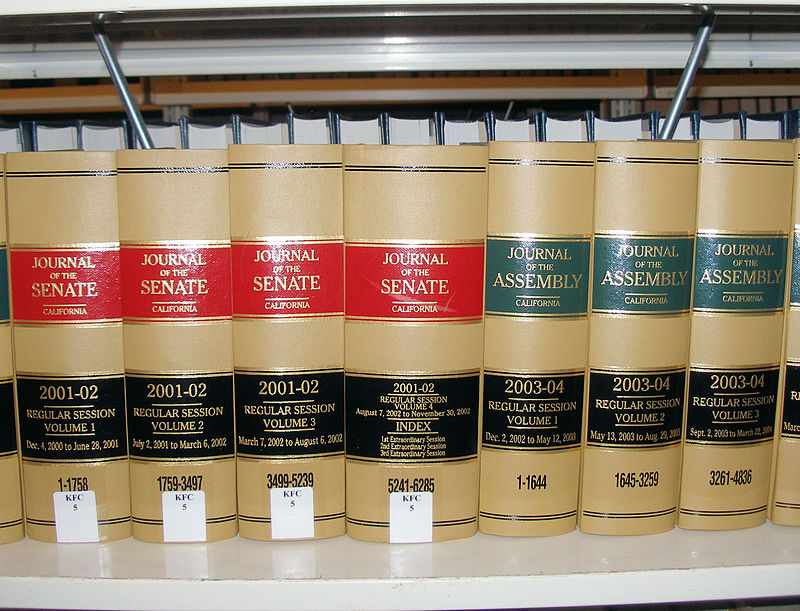

Legislative Daily Journals

The contents of the Assembly and Senate journals are prescribed. They are the proceedings of the respective houses. They are not only required to be kept, but also to be published so that the proceedings of each house shall be made known to the people. Constitutional amendments shall be entered in the journals and it is meant that the amendment must be copied or enrolled on the journal in full. The identical thing must appear on the journal, not a refence to it in any way.

Validity of Statutes in Journals

The validity of a statute does not depend upon the failure or omission of the journals to show affirmatively that such requirements were in fact complied with.

No Impeachment of Statutes by Journals

The validity of a statute which has been duly certified, approved, enrolled, and deposited in the office of the secretary of state cannot be impeached by a resort to the journals of the legislature.

Limits on Legislative Pensions

Although the portion of the proposition which placed limits on pensions was invalid, the remaining provisions of the measure, dealing with the number of terms of office and legislative expenditures, could be given effect without regard to the invalidity of the provision with respect to pensions, and that provision would be severed.

Standing to Challenge Constitutional Amendment

Voters and former state legislators had standing to raise a facial challenge to a state constitutional amendment imposing budget and term limits on state legislators. The challenge did not call for an advisory opinion because a successful challenge would affect the plaintiffs’ ability to run for office and to vote for termed out legislators.

Weighing Competing Interests

The Legislature’s essential function under the state constitution of making law by statute embraces the far-reaching power to weigh competing interests and determine social policy. The existence and nature of any statutory time bar in criminal cases, the decision to make any statute retroactive, and the enactment of rules regulating the dismissal and refiling of criminal counts are products of competing policy choices which are within the Legislature’s essential function of making law.

Difference Between Bills and Resolutions

A statute declares law and if enacted by the legislature it must be initiated by bill, passed with certain formalities, and presented to the governor for signature; a resolution does not require the same formality of enactment and is not presented to the governor for approval.

Limited Mandate to Administration Agency

Legislative enactment that limits the mandate of an administrative agency or withdraws certain of its powers is not necessarily suspect under the doctrine of separation of powers. When the Legislature has not taken over core functions of the executive branch and has exercised its authority in accordance with formal procedures set forth in the State Constitution, such an enactment normally is consistent with the checks and balances prescribed by the Constitution. Statutes enacted did not signify that the Legislature had taken over core functions of the executive branch, but constituted an expression of the Legislature’s essential duty to devise a reasonable budget. The Legislature’s power of appropriation includes the power to withhold appropriations and neither an executive administrative agency nor a court has the power to require the Legislature to appropriate money.

Amending Bills

A section of the code may be amended by reference to its number.

Changing Prior Statutes

The Legislature may amend existing laws by enacting codifications which substantially change the phraseology or punctuations of prior statutes.

Effective Dates of Statutes

A statute has no force whatever until it goes into effect pursuant to the law relating to legislative enactments and it speaks from the date it takes effect and not before.

Operative Date Specified and Urgency Clauses

Enactment of a law on its effective date only means that it cannot be changed except by the legislative process. The rights of individuals under its provisions are not substantially affected until the provision operates as law. The Legislature’s power to enact laws includes the power to fix a future date on which the act will become operative (i.e., to establish an operative date for a statute that is later than its effective date). A statute’s operative date is the date upon which directives of a statute may be actually implemented, whereas the statute’s effective date is considered that date upon which the statute came into being as existing law. The Legislature’s determination of urgency in enactment of the statute is final and the courts will not interfere with that determination unless no declaration of facts constituting the emergency is included in the act or unless the statement of facts is so clearly insufficient as to leave no reasonable doubt that urgency does not exist. Courts cannot say that the Legislature has not performed its constitutional duty, even though they may disagree with the legislature about whether declared facts constitute sufficient reason for immediate action. Under the state constitutional requirements for urgency measures, the second roll call vote was not needed to approve the urgency clause of a bill reducing the percentage of days of pre-conviction confinement even though the bill returned to its house of origin in drastically amended form.

Effective v. Operatives Dates

Under the California Constitution, a statute enacted at a regular session generally becomes effective on January 1 of the year following its enactment except where the statute is passed as an urgency measure and becomes effective sooner. In some instances, the legislature may provide for different effective and operative dates for a statute. The operative date of the statute is the date upon which directives of the statute may be actually implemented. The effective date of the statute is the date upon which the statute came into being as existing law. In determining the legal effect to be given an enactment that contains a different effective and operative date, a court must ascertain and promote legislative intent of enactment.

A Properly Adopted Bill Becomes Law

When a bill has been passed by the Legislature and signed by the Governor, it becomes a law and no evidence nor the judgment of any court can be allowed to modify or change its terms or effect or prevent or impair its complete operative force.

Allowance of Time for a Referendum

The purpose of the constitution that legislation with certain exceptions should not go into effect until 90 days after final adjournment of session at which it was adopted was to give the people an opportunity to express their judgment as to the merits of a statute by filing a referendum petition. The effective date of a statute may be made contingent upon a future event.

Postponing the Operative Date

The postponement of the operative date of the legislation does not necessarily mean that the Legislature intended to limit its application to transactions occurring after that date. Although the effective date of a statute, the date upon which the statute came into being as an existing law, and its operative date, the date upon which the directives of the statute may be actually implemented, are often the same, the Legislature may postpone the operation of certain statutes until a later time.

Legislature Can Set Operative Date

Unlike a statute’s effective date, which is determined according to immutable rules written into the state constitution, its operative date is the date upon which the directives of the statute are actually implemented, and is set by the Legislature in its discretion.

Statement of Facts in Urgency Clauses

Where there is any doubt as to whether the statement of facts constituting the necessity in emergency legislation states a case of immediate necessity, the doubt should be resolved in favor of the legislative declaration. The requirement that emergency legislation contain a statement of the facts constituting the necessity does not empower the judiciary to declare the declaration invalid unless it appears clearly and affirmatively from the statement of facts that a public necessity does not exist. A legislative declaration of urgency is binding on the courts.

Legislative Judgment Normally Final

When the Legislature has determined necessity of an urgency measure as authorized by the constitution, the Legislature’s judgment is final, unless no declaration of facts constituting the urgency or a clearly insufficient declaration is included.

Determining Need for Urgency Measures

The Legislature has authority to determine when urgency measures are necessary and recitals of necessity and public interest in legislation must be given great weight and every presumption made in favor of their constitutionality.

Single Subject Rule Liberally Construed

The constitutional single subject rule for statutes is to be liberally construed to uphold proper legislation and not to be used to invalidate legitimate legislation. The constitutional requirement that the single subject of a legislative bill shall be expressed in its title is to prevent misleading or inaccurate titles so that legislators and the public are afforded reasonable notice of the contents of a statute.

Purpose of Single Subject Rule

The single subject rule, by preventing misleading or inaccurate titles, serves the important purpose of ensuring that legislators and the public have reasonable notice of the scope and content of proposed statutes.

Germane Provisions

A legislative provision is germane for purposes of the single subject rule if it is auxiliary to and promotes the main purpose of the act or has a necessary and natural connection with that purpose. Legislation complies with the single subject rule if its provisions are either functionally related to one another or are reasonably germane to one another or the objects of the enactment. The single subject rule is satisfied if the provisions of the act are cognate and germane to the subject matter designated by the title and, if the title intelligently refers the reader to the subject to which the act applies, and suggests the field of legislation which the text includes. The Legislature may combine in a single act numerous provisions governing projects so related and interdependent as to constitute a single scheme and provisions auxiliary to the scheme’s execution may be adopted as part of that single package. The single subject rule is to be liberally construed to uphold proper legislation and not used to invalidate legitimate legislation. A statute must comply with both the requirement that it be confined to one subject and with the command that one subject be expressed in its title. The single subject clause has as its primary and universally recognized purpose the prevention of log-rolling by the Legislature (i.e., combining several proposals in a single subject bill so that legislators, by combining their votes, obtain a majority for a measure which would not have been approved if divided into separate bills).

Multiple Amendments in a Single Bill

Multiple proposed amendments in a single measure violate the separate vote provision when they are not germane to a common theme, purpose or subject.

Budget Bills and the Single Subject Rule

The single subject rule is not to receive a narrow or technical construction, but it is to be liberally construed to uphold proper legislation and not used to invalidate legitimate legislation. Budget bills that substantively change existing law violate the single subject rule. The budget bill may deal only with one subject of appropriations to support the annual budget and thus may not constitutionally be used to grant authority to a state agency that the agency does not otherwise possess or to substantively amend and change existing statutory law. The single subject rule essentially requires that a statute have only one subject matter and that the subject be clearly expressed in the statute’s title. Provisions governing projects so related and interdependent as to constitute a single scheme may be properly included within a single act. The Legislature may insert in a single act all legislation germane to the general subject as expressed by its title and within the field of legislation suggested thereby without violating the single subject rule.

Construing the Single Subject Rule

To minimize judicial interference in legislative branch activities, courts must construe the constitutional provision requiring that a statute embrace but one subject liberally. A provision is deemed germane to other provisions in a statute as would support a determination that the statute complies with the single subject rule providing that the statute must embrace but one subject. The purpose of the rule is to prevent legislators and the public from being entrapped by misleading titles to bills whereby legislation relating to one subject might be obtained under the title of another.

Budget Bills and Line-Item Vetoes

Budget bills that substantively change existing law violate the single subject rule because a substantive bill making a change to existing law can be vetoed in its entirety by the governor and incorporating such a bill into a budget bill makes it impossible for the governor to properly exercise his veto. The legislative power is circumscribed by the requirement that the legislative acts be bicamerally enacted and presented to the head of the executive branch for approval or veto. A bill making an appropriation of zero dollars is not a substantive act but is simply an act of non-appropriation which, by operation of the statute, has the automatic legal effect of freeing local agencies from the obligation to implement the mandate for that year. When there is a lump sum appropriation intended for multiple purposes, but does not specifically allocate amounts to each of these purposes, the governor may use the line-item veto to reduce the lump sum amount, but the governor may not attribute the amount of the reduction to a specific purpose. The constitutional provision requiring the Legislature to either fund or suspend local agency mandates did not prohibit the governor from applying the line-item veto to reduce an appropriation funding a local agency mandate to zero. When the governor exercises the power of the veto, he is acting in a legislative capacity and he may only act as permitted by the Constitution. The governor possesses the constitutional authority to reduce or eliminate an item of appropriation in the budget bill passed by the legislature. The Legislature cannot shield an appropriation from the Governor’s line-item veto simply by not using the language of appropriation in the budget bill.

Governor Acting in a Legislative Capacity

The governor acts in a legislative capacity in submitting the annual budget bill to the legislature and in approving it after its adoption.

Limitation on Budget Bills

The Budget is fully subject to scrutiny under the single subject rule and its subject is the appropriation of funds for government operations and it cannot constitutionally be employed to expand a state agency’s authority or to substantively amend and change existing statute.

Power of Appropriations

The power to appropriate public funds belongs exclusively to the Legislature. The line item veto does not confer the power to selectively veto general legislation. The Governor has no authority to veto part of a bill that is not an item of appropriation. The Supreme Court would take judicial notice of Legislative Counsel opinions.

Legislature Can Create Offices Without Funding

The Legislature is not precluded from creating agencies or offices, including courts and judgeships, without funding the initial fiscal year, but rather legislatures first decide whether the need for the new agency or office needs to be established and they then decide whether and how to prescribe the funding.

Reenactment Rule

When adding a new code section, the Legislature is not required to re-enact other code sections that were affected by the change.

Appropriations Bills and Reenactment Rule

Appropriations measure violated the constitutional reenactment rule and did not effectively amend an initiative despite being passed by four-fifths vote of the Legislature where there was no change to the statutory allocation language. The purpose of the constitutional reenactment rule, which prohibits amending a section of statute unless the section is reenacted as amended, is to avoid enactment of statutes in terms so blind that legislators themselves are deceived in regard to their effect. The rule clearly applies to acts which are in terms amendatory of some former act. It does not apply to the addition of new code sections or enactment of entirely independent acts that impliedly affect other code sections.

Highest Chapter Number Rule

The highest chapter number rule does not violate the division of powers doctrine.

Judiciary Does Not Play a Role in Lawmaking

The courts may not order the Legislature or its members to enact or not to enact legislation, nor may it order the governor to sign or not to sign legislation.

Governor’s Actions on Bills

A bill may become a law by signature of the governor after passage by the legislature, or by the governor retaining it without signing it, and his causing a certificate of the fact to be made on the bill by the secretary of state and depositing the bill with the laws in the office of the secretary or by passage of the bill over the governor’s veto.

Governor’s Exclusive Power

The Governor has exclusive discretion to sign or veto bills passed by the legislature and he also has the power to reduce or eliminate one or more items of appropriations.

Limit on Governor’s Power

The governor is not empowered to decide as to how many subjects are contained in a bill presented to him for signature and to veto parts of a bill which he determines constitute separate subjects.

Line-Item Veto Not Applicable to All Bills

As to non-appropriation measures, the governor is permitted either to accept or reject a bill in its entirety, but he may not, by qualifying his approval, exercise what is in effect an item veto.

Concurrent Resolution

A concurrent resolution of the legislature, passed at a special session, and purporting to validate, affirm and authorize the prior action of the senate in creating an interim committee to sit after adjournment sine die, was ineffective for that purpose. If an interim committee appointed by the legislature is to function lawfully after adjournment of the legislature, it can be created only by statute.

Civil Process Exemption for Legislators

The constitutional provision exempting legislators from civil process during the legislative session applies generally and without qualification as to kind or subject matter of a lawsuit and it may not be diluted by interpretation to a restricted class of lawsuits.

Power of the Legislature

Unlike the U.S. Congress, which possesses only those specific powers delegated to it by the U.S. Constitution, the California Legislature possesses plenary legislative authority except as specifically limited by the California Constitution and lying at the core of that plenary authority is the power to enact laws. A state statute passed by the Legislature to place an advisory question on the statewide ballot was a valid exercise of the Legislature’s implied power to investigate the necessity to exercise its power to petition for a federal constitutional change, even though the Legislature had already submitted to Congress a call for a national convention to pass an amendment. The state constitutional provision stating that the Legislature may provide for the selection of committees necessary for the conduct of its business does not implicitly prohibit the Legislature from using advisory ballot measures to determine the electorate’s position on whether the Legislature should exercise its power to petition for federal change. For bills to be “bills identified as related to the budget in the budget bill” within the meaning of the constitutional provision excluding such identified bills from the supermajority vote requirement for appropriations, the bills must not only be related to the budget bill, but also, they must be identified at the time the budget bill is passed by the Legislature. “Spot bills” that contain no substance when the budget bill is passed are not “bills identified as related to the budget in the budget bill” within the meaning of the constitutional provision excluding such identified bills from the supermajority vote requirement for appropriations, even if the budget bill refers to the spot bills by number.

Lawmaking Authority Is Plenary

The state constitution’s grant of lawmaking authority to the Legislature is plenary except for the reserved rights of initiative and referendum which empowers that body to exercise this authority in any manner that is not expressly or through necessary implication prohibited elsewhere in the constitution. The budget bill is limited to the one subject of appropriations to support the annual budget. The Legislature’s estimate of revenues used to determine whether the state budget complies with the balanced budget provision of the state constitution may include revenue sources not yet authorized in existing law or in enrolled legislation. The Controller may not withhold legislators’ salary on the basis that a budget bill that the Legislature has designated as “balanced” is not in fact balanced under the constitutional provisions stating that legislators forfeit their salaries during the period that a balanced budget bill is past due, since such an audit is not within the Controller’s statutory power to determine the lawfulness of a disbursement of state money. An action brought by the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the Assembly for declaratory judgment that the Legislature had complied with the requirement to pass a balanced budget bill to preclude withholding of legislators’ salaries presented an actual controversy as required for declaratory relief. The Legislature’s estimate of revenues used to determine whether the state budget complies with the balanced budget provision of the state constitution may include revenue sources not yet authorized in existing law or in enrolled legislation.

Power to Eliminate Existing Laws

The legislative power that the state constitution vests is plenary and a corollary of the legislative power to make new laws is the power to abrogate existing ones. Courts start from the premise that the Legislature possesses the full extent of the legislative power and its enactments are authorized exercises of that power, and only where the state constitution withdraws legislative power will courts conclude an enactment is invalid for want of authority. The reenactment rule’s purpose is to make sure legislators are not operating in the blind when they amend legislation and to make sure the public can become apprised of changes in the law.

Judging Qualifications of Its Members

Under the separation of powers doctrine and the provision of the state constitution vesting in each house of the legislature the sole authority to judge the qualifications and elections of a candidate for membership in that house, California courts lack jurisdiction to judge the qualifications of a candidate for a primary election for a state senate seat who allegedly had not resided in his district for at least one year as required by the state constitution. It is the judiciary’s role to interpret the law, including the constitution, but it is not the judiciary’s role to judge the qualifications and elections of candidates for membership in the legislature. The Legislature cannot delegate to the courts its prerogatives under the state constitution to judge the qualifications and elections of its members.

General Versus Special Laws

Under the constitutional prohibition of special legislation, a law is “general” when it applies equally to all persons in a class founded upon some natural, intrinsic or constitutional distinction, and it is “special” if it confers particular privileges or imposes peculiar disabilities or burdensome conditions, in the exercise of a common right upon a class of persons arbitrarily selected from the general body of those who stand in precisely the same relation to the subject of the law. The test for determining whether a statutory classification violates the constitutional provision stating that a “local or special statute is invalid in any case if a general statute can be made applicable” is substantially the same as that used to determine constitutionality under the equal protection clause. The constitutional prohibition of special legislation does not preclude legislative classification but only requires that the classification be reasonable.

- Exemptions from Tax Withholding in California - July 23, 2024

- General Provisions of California’s Evidence Code - July 22, 2024

- Judicial Notice Under the California Evidence Code - July 21, 2024