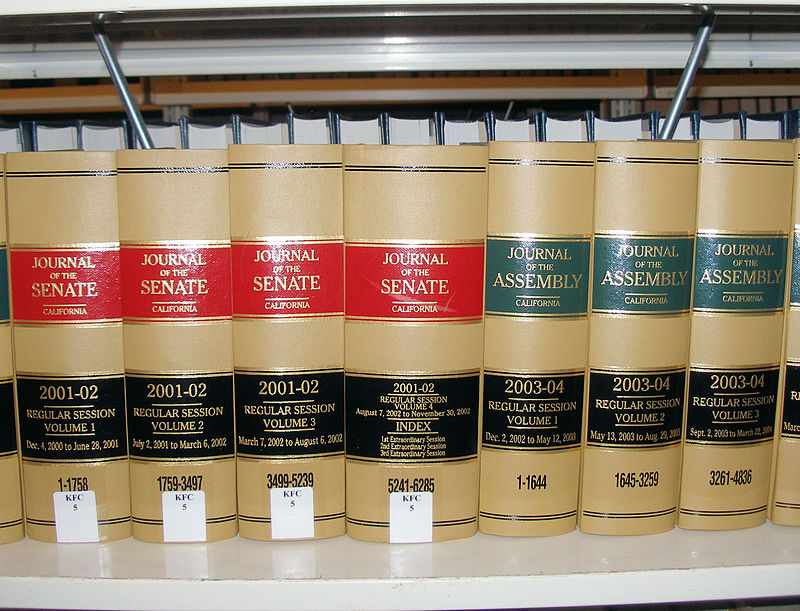

Journals of the California Legislature. (Photo: Wikipedia)

The Enrolled Bill Rule in California

Part of the governing rules between the legislative and judicial branches ensure that legislative rules and procedures are respected by the judiciary

By Chris Micheli, October 9, 2020 6:23 am

In general, the judicial branch is loath to review the record keeping practices of the Legislature to determine the validity of statutes. This limitation on judicial inquiry is known as the “Enrolled Bill Rule” and this legal doctrine holds that, if an act of the Legislature is “properly enrolled, authenticated and filed,” then it is presumed that “all of the steps required for its passage were properly taken,” and “even the journal of the Legislature is not available to impeach it.”

Based upon the California Constitution’s enumerated separation of powers doctrine, the reasoning behind this judicial limitation is that the judicial branch should not impinge on the constitutionally enumerated power of the legislative branch to govern its internal affairs. Despite some critics of this legal principle, as recently as 2009, courts have concluded that this Rule is still “in full effect in California.”

Capitol observers note that the Enrolled Bill Rule is part of the governing rules between the legislative and judicial branches of state government and ensure that legislative rules and procedures are respected by the judiciary. Basically, when a legal question is raised with a court whether a bill that was passed by the Legislature and sent to the Governor’s Desk, the legal inquiry is whether the requirements of California’s Constitution, found in Article IV, Section 8(b), where complied with by the legislative branch.

The provisions of Section 8(b) include that (1) each bill be read by title on three days in each house unless the house dispenses with the requirement by rollcall vote entered in the journal and (2) no bills are to be passed unless the bill with amendments has been printed and distributed to the members. If these constitutional requirements were not met, then a court could invalidate a statute passed by the Legislature.

Existing state case law provides that, once a bill has been authenticated and enacted, it would violate the separation of powers doctrine found in the state Constitution, Article III, for a court to use extrinsic evidence to determine that the Legislature failed to satisfy the constitutional requirements for enacting a statute.

Almost 100 years ago, the California Supreme Court ruled in Taylor v. Legislature (1927) 201 Cal. 327, 332, that “a statute, properly enrolled and authenticated, conclusively establishes not only the contents of the law but the due performance of all steps requisite to its passage by the legislature. This is the general law and has long been the rule of decision in this state.”

This principle, known as the Enrolled Bill Rule, was described by the court in 1927 as having “long been the rule of decision in this state,” in that the rule was first articulated by the California Supreme Court in Sherman v. Story (1866) 30 Cal. 253. In that 1866 decision, the court refused to consider uncontradicted legislative journals and oral testimony alleging that certain proposed amendments that were rejected in the Assembly were nonetheless, and apparently mistakenly, incorporated into the act by the enrolling clerk of the Senate.

Thereafter, in County of Yolo v. Colgan (1901) 132 Cal. 265, the California Supreme Court rejected a claim that, based on an entry in the Senate Daily Journal, a statute had not received the requisite number of votes for passage and was thus invalid; in so ruling, the court cited the separation of powers doctrine, concluding that “while the constitution has prescribed the formalities to be observed in the passage of bills and the creation of statutes, the power to determine whether these formalities have been complied with is necessarily vested in the legislature itself…”

In addition, in Planned Parenthood Affiliates v. Swoap (1985) 173 Cal.App.3d 1187, a conference committee on the annual Budget Bill proposed to each house a version of the Budget Bill that excluded a provision, Section 33.35, and the conference committee proposal was approved by the Senate and Assembly and duly enacted into law. Notwithstanding the discovery that, due to staff error, Section 33.35 had not in fact been removed from the Budget Bill proposal, the court ruled that it lacked the power to strike the section from the enacted Budget Bill.

Citing the “salutary principle [that] has long been established in California that the judicial branch may not go behind the record evidence of a statute,” the court ruled that because Section 33.35 received the necessary approval of each house of the Legislature and was “duly enrolled and approved by the Governor,” it could not be impeached by extrinsic evidence.

Nonetheless, the California courts have identified one exception to the Enrolled Bill Rule. That exception was discussed at length in People ex rel. Levin v. County of Santa Clara (1951) 37 Cal.2d 335, a case in which a defect in the local adoption of charter amendments was evidenced by a recitation on the face of a resolution adopted by the Legislature addressing that local enactment. In Levin, the court cited the general principle that, “when an act of the Legislature is valid on its face, properly enrolled, authenticated and filed, it is conclusively presumed that all of the steps required for its passage have been properly taken; even the journal of the Legislature is not available to impeach it.”

The appellate court then engaged in a discussion of case law and treatises reviewing the scope of the Enrolled Bill Rule, concluding as follows: “Thus the holding is that if irregularity in the proceedings by the local authorities appears on the face of the legislative resolution, the approval by the Legislature is not conclusive, as it would be, if it was not revealed by the resolution.” In Levin, the court deemed this exception to the Enrolled Bill Rule to apply for the reason that the procedural defect in the local adoption of charter amendments was evidenced on the face of the resolution adopted by the Legislature.

- Commercial Fishing - February 26, 2026

- Are These Extra Words Needed in California Statutes? - February 25, 2026

- Attorneys-in-Fact in Probate - February 25, 2026