Wildwood Canyon State Park (Photo: Evan Symon for California Globe)

The Sordid History of the California State Beach Smoking Ban: Part II – The Environmental Damage of SB 8 and AB 1718

Stolen Bills, environmental damage, and the mysterious pro-smoking amendment

By Evan Symon, September 18, 2019 2:47 pm

On the eve of the signing of SB 8 and AB 1718, the bills that would ban smoking in state beaches and parks, the California Globe has uncovered new information about the developments, changes, and consequences of the bills. In an exclusive three-part series, we will bring to light the ways in which the bills with near-universal support were harmfully doctored and betrayed the trust of many of its one time supporters.

In this second part of our series on the state beach and park smoking ban bills, we dug into the environmental damage that can be caused by the bills passage. In particular, we look at how the amendment to SB 8 (and subsequently AB 1718) will not only allow most smoking to continue, but also how catastrophic it will be to the environment and to the health of state park and beach visitors.

In early September, SB 8 was well on its way to being accepted mostly intact. But over the course of three days the bill was amended in the assembly, bringing mysterious last minute changes.

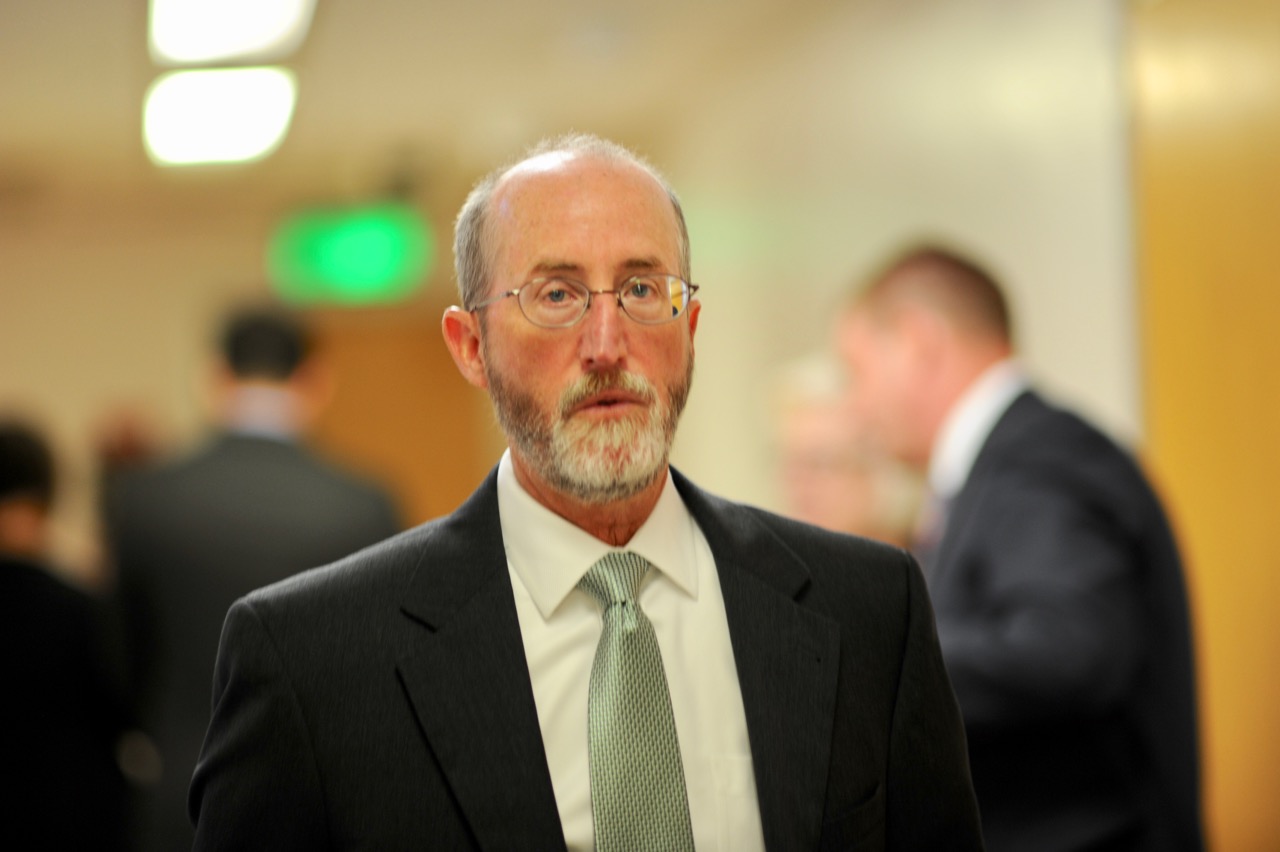

Keeping the fine changes from previous bills for smoking on a beach or in a park outside the exempted areas from $250 to $25 is a major source of contention. Dr. Jeremiah Mock, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco who researches tobacco reduction in California and Asia, shared his concern.

“Changing the fine from $250 to $25 is not consistent with other laws,” Dr. Mock told the Globe. “In California, the minimum for littering is in the hundreds. When you drive in the carpool lane, violations can be over $300. Parking tickets can be just as much. But with beach smoking fines to be so much smaller, it makes a health and safety risk to others seem like a smaller offense.”

Mike Lynch, the President of the California State Park Rangers Association (CSPRA), also agreed, telling the Globe that the fine isn’t consistent.

“This isn’t even a slap on the wrist. Remember, the ranger in the field will have to enforce the fine. This creates a lot of problems. Rangers can’t be everywhere at once, and the fine is so low that many people will take the chance. And that’s nothing compared to the religious exemption.

He refers to the religious exemption, a part of the amendment which allows smoking if it’s a part of some religions. And this part of the bill is also a major source of contention for those who had supported the original bill. Scott St. Blaze, an Environmental Activist who helped write the original language of the current bills, explained the issue with the exemption.

“The religious exemption which would allow for anyone to smoke any kind of plant product, anywhere within a California State Park, as long as the user claims the action to be ‘part of a good faith practice of a religious belief,’” said Blaze. “There are over 4,000 different religions in practice today. How the hell would our rangers and the courts even begin to try to sort out just what exactly someone’s religious beliefs are and whether or not what was done, was done in “good faith”? The language fails to make it clear as to who the burden of proof would be on.”

“There are NO other smoking bans in the entire nation with a religious exemption,” St. Blaze continued. “Should SB 8 or AB 1718 pass into law, it could very easily open the door to weakening every single smoking ban already in place, nationwide.”

CSPRA president Lynch noted other concerns for rangers in the field who will have to enforce the ban. “From a practical point of view of the religious exemption, all a person would have to do while smoking is declare that it is part of their religious belief. When I testified before the Assembly, I made sure to bring up that the use of the word ‘belief’, as it stands in the current general smoking ban, would allow someone to light up right in the hearing room.”

But both authors (Senator Steve Glazer (D-Orinda) and Assemblyman Marc Levine (D-San Rafael) told the Rangers Association that they didn’t want anything to change any language in the bills, as this was how the bills passed last session.”

Amazingly, smoking during religious practices that might not normally be permissible are already allowed through the use of special permits in California State Parks.

“Native Americans and quasi-religious special events happen in state parks, and they’re allowed and could continue to be allowed to smoke, under permit.” Lynch explained. “State Parks issues thousands of special events permits each year to events big and small. Activities are already allow for religious purposes as long as they get a permit.”

With the Amendment, anyone can claim to be smoking for a religious reason. And it could be very problematic. How can a ranger in the field determine if it’s for a religious purpose or not? If the “say it is part of your religious belief” reason makes it on social media, and it will, thousands of regular smokers will have a ready-made out to allow them to smoke anywhere in state parks. So, if a ranger issues a ticket to someone for smoking and the person right next to them doing the same thing gets ‘off’ for expressing a religious belief, it causes a lot of problems for the field ranger. It’s not even-handed and if it goes to court, the ticketed person could easily plea that ‘I got a ticket for that and the other person didn’t, even though we’re both smoking for our religion.’ If the judge agrees, then the word will quickly get around that you can win in court for any smoking ticket by ‘taking the religious belief’ defense. It would be a mess. With Social media, this would quickly become common knowledge. Smokers are very motivated to find ways to smoke.”

“And it could even lead to lawsuits for the field ranger trying to do their job because they couldn’t dispute proof of their ‘belief,’ which is a legal issue on its own.”

Jensen Jennings, a former aide to Senator Glazer who had been a part of earlier version of SB 8, noted the changes in the wording. Specifically he pointed out how SB 386 carefully worded out who was covered under religious usage.

“In the 2017 version, the bill only allowed for well-defined religious usage,” Jensen said. “SB 386 in 2017 said ‘Smoke’ or ‘smoking’ does not include the use of a cigar, cigarette, or pipe, or any other lighted or heated tobacco or plant product used for ceremonial purposes by a federally recognized Native American tribe or a non-federally recognized California Native American tribe listed on the California Tribal Consultation List maintained by the Native American Heritage Commission.”

“I would like to see a bill next year that defines what a good faith religious belief/ ceremony is. I believe there should have to be some proof of legitimate usage of anything that can be smoked,” Jensen added.

And while an extremely problematic lowering of the fine and an easily fixed religious exemption change are in themselves issues, the biggest change to SB 8 was the one with the largest health and environmental changes: the allowance of people being able to smoke in paved areas.

Dr. Mock has researched the issue for years and said that allowing smoking in roadways and parking facilities would undermine the legislation, as well as fail to protect the public health and natural environment.

“Allowing smoking in roadways and cars worries me the most,” explained Dr. Mock. “We’ve seen in preliminary observations that a lot of tobacco waste gets left in lots and roadways. It’s common for people to park and then flick the butt on the ground. It builds up.”

“It’s particularly problematic at beaches. Lots there are designed on a slope for drainage, so this waste is swept into streams and out into the ocean. It causes a substantial impact.”

“Cigarette butts in state parks are a huge item,” added CSPRA President Lynch. “A lot of time and money. In parking areas they concentrate in a certain way. We’ve seen how people legally smoking will crush them on the ground, with parking lots filled with them. With the ban, they’re all going into the same place. The parking lot and the roads straight to the ocean.”

Dr. Mock also noted the health impact.

“The amendment would lead to a lot of secondhand smoke,” Dr. Mock continued. “In a confined area, it drifts around. It’s like a smoking section in a restaurant or the back of the plane during the days of smoking on airplanes. That causes respiratory problems and triggers asthma.”

“It also starts to normalize smoking again. Thanks to the California Tobacco Control Program, smoking has declined. We’ve denormalized smoking in buildings, workplaces, restaurants, and bars. We don’t even think about it any more. We wouldn’t give any allowances for smokers that would harm the public’s health.”

“This would be an allowance. It would be the smoking section for beaches. It would normalize it.”

Dr. Mock pointed out how e-cigarette waste is also leaving its mark, telling the Globe, “We’re finding more and more e-cigarette waste now like discarded pods, bottles, and vape pens. In Japan disposable IQOS heat sticks with plastic filters and powdered tobacco are everywhere on beaches, and we could be seeing that as well.”

There was also the issue of fires.

“This legislation would also potentially increase fire hazard because smokers who smoke in roadways and parking facilities flick their butts into dry grass and vegetation along the perimeter roadways and parking facilities,” noted Dr. Mock.

For CSPRA president Lynch, a ranger, this is a particular issue for state parks.

“A lot of park roads go through places with fire danger. If you’re in a paved lot or walking or driving on paved road, flick out a cigarette into dry grass, that’s a huge problem.”

“It means more fires.”

Lynch also has a concern for the safety of the smokers themselves.

“Ten percent of Californians smoke. That’s a lot of people. Without a park or camp site to smoke in, they’re allowed to smoke in paved areas, and this includes roads. Not only will this lead to a lot of questions of ‘Where can I stand where it’s paved?’ but it will force smokers to more dangerous places, even right into the traffic lane, as a large percentage of park roads do not have paved shoulders.”

“We’ve seen that smokers are very motivated to find places to smoke. When we moved the limit away from buildings they’re allowed to smoke from outside the doorway to 50 feet, they found convenient places 50 feet away.”

“In this case, with paved areas, it means traffic danger on the roadway, since that might be the only paved area. They’ll be pedestrians at risk, and we might see lines of smokers outside of campsites on the side of or in the road smoking. They’ll be in big danger of being hit by a car.”

It also means rangers will need to try to draw some pretty narrow lines on where they can or cannot smoke based on their safety, where a pedestrian can be on a roadway, and where the paved area begins and ends.

With the new amendment to SB 8 also adding health dangers, a substantial environmental damage in the making with tobacco waste harming coastlines and waterways, fire dangers, and a public safety danger of people being forced into areas with moving vehicles, many wondered how such an amendment was passed. Most people the Globe interviewed called it a mystery.

After all, how could a bill that started with such a public good in mind turn into such a potentially harmful bill that was changed for seemingly no reason?

“That’s easy” said ‘Dana,’ a source who works in the State Capitol in Sacramento. “The tobacco lobby got to them.”

Next: Part III – The Mysterious Pro-Smoking Amendment

Previously: Part I – The Stolen Bills

- San Diego Country Supervisor Jim Desmond Calls San Diego New Epicenter Of Illegal Crossings By Migrants - April 27, 2024

- Oracle Moving Headquarters Out Of Austin Only 4 Years After Moving Out Of California - April 26, 2024

- Congressman Adam Schiff Robbed of his Luggage in San Francisco Car Break In - April 26, 2024

One thought on “The Sordid History of the California State Beach Smoking Ban: Part II – The Environmental Damage of SB 8 and AB 1718”