Santa Ana train station. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Who Runs the City of Santa Ana, Anyway?

Santa Ana’s officially recognized unfunded pension liability was $637 million

By Edward Ring, June 1, 2020 7:03 am

With rare exceptions, most cities in California are run by public sector unions. There is the appearance of democracy, with public employees accountable to elected officials, who in turn are accountable to voters, but appearances can be deceiving. Because political campaigns to attract voters require money, and public sector unions have money. Lots of money. In California alone, public sector unions collect and spend over $800 million dollars per year.

Through slick advertising and public relations campaigns, money buys votes, and voters elect politicians. Especially in California’s big cities, public sector unions have perfected the art. Ask any local California politician why they have agreed to support another tax increase to pay for the latest pay and benefit increase to which they have also agreed. If they’re honest, their answer will be swift and unequivocal: Because if I don’t do what they tell me to do, the unions will spend whatever it takes to defeat me in the next election.

Cecilia Iglesias, former councilwoman for the City of Santa Ana, just learned this lesson the hard way. She wasn’t just defeated in the next election, she was recalled in the middle of her term. According to the Orange County Register, the Santa Ana Police Officers Association spent $341,000 on the campaign to oust Iglesias, and the city had to spend an additional $710,000 to conduct the special election.

The reason for the recall effort will vary depending on who you ask. According to the unions who backed the recall, Iglesias was corrupt. According to Iglesias, the recall was retaliation for her vote against granting the Santa Ana police $25 million in raises. Regardless of who you believe, Iglesias was right to oppose increasing police pay in her city. They can’t afford it. Not back on February 6 when the city council approved these pay increases, and certainly not today.

State Senator John Moorlach, a supporter of Iglesias and the only Certified Public Accountant currently serving in the California State Legislature, explained the difficult financial challenges facing the City of Santa Ana. In a guest editorial that appeared in the Orange County Register on April 24, Moorlach wrote, “Even before the coronavirus struck the world, city finances were abysmal. Santa Ana’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) for June 30, 2019 showed an unrestricted net deficit of $471 million.”

Moorlach’s right. It’s going to take the City of Santa Ana long time to climb out of a hole that deep. A recent analysis by Truth in Accounting (TIA), a nonprofit government finance watchdog group, gave Santa Ana a “D” grade for its fiscal health. But like a sick person with a glowing suntan, Santa Ana does not show obvious signs of financial distress.

When Cecelia Iglesias ascended into the Moorlachian realm of high finance, down in the gutters and alleys of retail vote grabbing, street fighting politicians and their union backers were able to take her down.

Yes, Santa Ana has an “unrestricted net deficit of $471 million.”

Yes, Santa Ana’s officially recognized unfunded pension liability was $637 million.

Yes, that was based on their 6/30/2019 financial reports, which – thanks to snail like performance of pension actuaries – only reported the pension liability as of 6/30/2018.

Yes, even before the pandemic, many analysts would have pegged Santa Ana’s unfunded pension liability at over a billion dollars, because the official estimates have a history of being too optimistic.

And yes, the pandemic has caused an economic shutdown that is killing investment returns, which means Santa Ana’s unfunded pension liability is far worse.

So what?

What’s an “unrestricted net deficit.”

And what’s an unfunded pension liability?

In California’s cities, down on the street, and on the mailed placards that campaigners saturate the precincts with, it’s easy to dismiss warnings about the pensions as agenda driven alarmism. After all, in

Santa Ana, during the fiscal year ended 6/30/2019, the city collected $581.7 million and spent $494.4 million. They made $24.2 million more than they spent. Where’s the problem?

This is what fiscal reformers are up against. Public agencies are resilient entities. Whenever a deficit looms, the public sector unions and their kept local politicians will endlessly propose new taxes and borrowing. Normal voters are unlikely to understand the significance of pension storms on the horizon when the sun is shining on their front lawn. And politicians know that by the time the hailstorms arrive, they’ll be long retired.

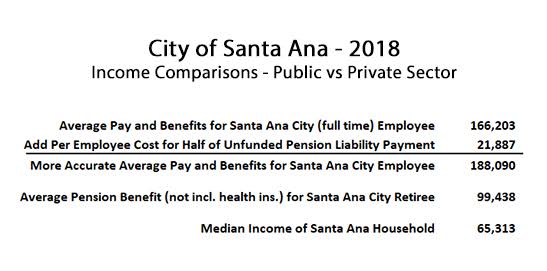

Maybe for a change, just shine a light on the compensation profiles in Santa Ana, a city where the median household income in 2018 was $65,313.

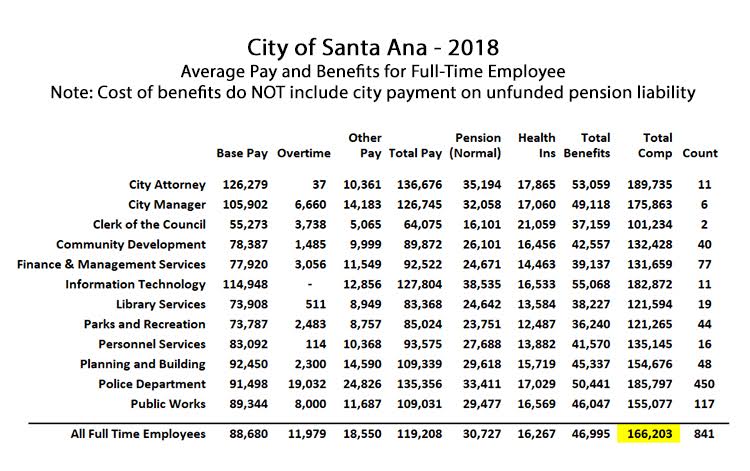

How does that compare to the pay and pensions received by Santa Ana’s public servants? Using data provided by the California Office of the State Controller, the following table lays this out by department, taking into consideration only full-time employees of the city. As can be seen, when the value of benefits is included, working for the City of Santa Ana turns out to be a very rewarding profession. During 2018, the average pay and benefit package was worth $166,203.

Not included in this data is the amount required to pay down that $637 million unfunded pension liability, an amount which is likely to swell to over a billion dollars when the economic losses from the pandemic recession are fully played out.

This is a controversial issue, because public employee unions claim the payment on the pension system’s shortfall should not be considered part of an employee’s compensation. On the surface, this argument is ridiculous, because nobody else collects these pensions. If the system had been funded adequately to begin with, those “normal” payments would have been considered part of the employee’s benefits.

On the other hand, some of the payments being made today in an attempt to slowly restore adequate funding to the pension system are for retired employees. Why should current employees have that portion of the unfunded payment be considered part of the cost for their pension benefit? This is a reasonable argument, but before taking that into account, using data provided by CalPERS, it’s worth having a look at just how much this unfunded pension payment is costing the City of Santa Ana.

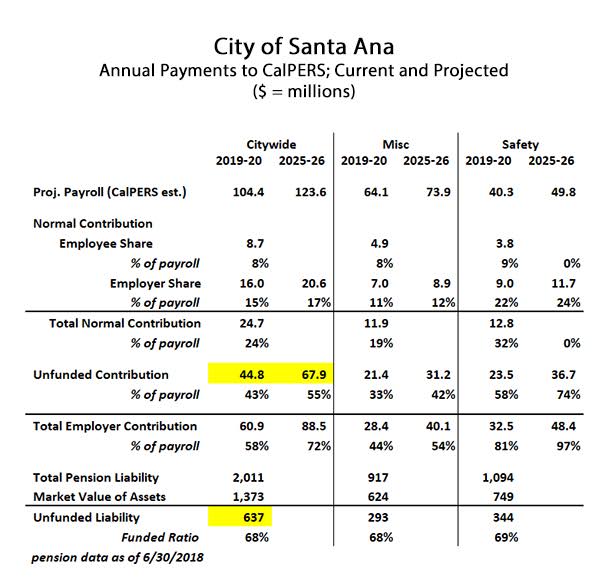

As can be seen in the yellow highlighted cells in the above chart, this year, the City of Santa Ana is going to pay nearly $45 million just to lower the amount of their unfunded pension liability. By the time of the 2025-26 fiscal year, according to CalPERS own data, that amount will increase to nearly $68 million.

It is important to emphasize that these figures are optimistic for at least two reasons. First, Santa Ana’s officially recognized unfunded pension liability existing at the end of the last fiscal year was despite an uninterrupted eleven year bull market in stocks, bonds and real estate. At the end of a bull market this long, pension systems should be overfunded, not sitting on a funded ratio of only 68 percent. Second, the global economic “correction” currently being experienced across all asset classes, thanks to the pandemic shutdown, is worse than anyone expected and could take years to unwind.

How resilient municipal finances will be during an economic downturn is impossible to predict. But it is wrong to award salary increases whenever the financial means exist to pay them. Instead, the most important context should always be consideration for the citizens being served. How much are hard working members of the taxpaying community earning? How much were they earning up until now, and how much will they be earning in the uncertain times ahead? The next chart brings this into stark focus.

Notice the second row on this chart, which adds in the per employee cost for half of the city’s annual unfunded liability payment. This is a fair calculation, which if anything understates how much, per active employee, these pensions are costing the City of Santa Ana. Anyone interested in reviewing these calculations can download the spreadsheet from the website of the California Policy Center.

The next time public employee unions attack a candidate or an elected official for objecting to granting another pay raise, providing voters with information on just how much they are already earning should be front and center in the discussion.

For example, the average full time employee of the City of Santa Ana makes pay and benefits of $188,090 per year. The average full-career retiree of the City of Santa Ana collects a pension of $99,438 per year. These numbers would be unbelievable if they weren’t so well documented.

Perhaps voters should be handed rosters showing the actual amounts being paid to the City of Santa Ana’s active workers. This is easily done these days, using information provided by the website Transparent California. All of their information comes directly from the California State Controller, or directly from California’s many public employee pension funds including CalPERS.

Use Transparent California to have a look at the the City of Santa Ana’s individual pay and benefits reported for 2019. Note “pension debt” is estimated per employee based on 100 percent of the city’s unfunded pension contribution. As discussed, a more conservative method was used in this article and its underlying analysis. Either way, the numbers are staggering. And have a look at how much, per individual, is being paid to their retirees.

Voters should see this information. Then simply ask them: Is this fair?

The next time public employee unions attack a candidate or an elected official for objecting to another pay raise, providing voters with information on just how much they are already earning should be front and center in the discussion.

Of course we want to pay our public employees well. But we also want to respect the citizens they serve.

- Ringside – Building the Abundant Water Coalition - March 5, 2026

- Ringside: Can Energy and Water Interests Find a Common Agenda? - February 26, 2026

- Ringside: What Will California Gas Prices Do in 2026? - February 19, 2026